'The prostate cancer support groups are filled with men who tried to get a test and couldn’t'

Despite an ambition to catch cancers sooner, many prostate cancer patients are still being given devastating late diagnoses

On a Friday evening as he prepared to sit down with his family to watch Scotland’s opening match of Euro 2024, Colin Pearse took a call that would change his life. For some time he had been concerned about a need to rush to the toilet to pee as well as niggling pain in his hip and back, all symptoms which could be put down to ageing and the relentless passing of time which leads our bodies to break down in myriad ways.

But this time something felt different. After some research of his own, Colin convinced his GP to give him the test commonly used to help spot the signs of prostate cancer. Initially the doctor was dismissive about the need for the test, which checks the level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the blood. But when he rang with the results, he sounded worried. For men of his age, a score above three is considered abnormal – Colin’s PSA was 40.

Fit and careful about what he eats, Colin is in his mid-50s but looks 10 years younger. Even now, more than a year on from his diagnosis, you would not know he is ill. While a biopsy confirmed the presence of cancer, an MRI scan showed it had not spread. He was told he would need an operation to remove his prostate, a life-changing procedure for which there was a nine-month wait on the NHS. But alarmed about his high PSA reading, a surgeon told Colin to use his private medical insurance. Within a week of going private, a scan confirmed the cancer had metastasised and was in his hip, thorax and spine. Despite his healthy lifestyle, Colin was now a stage four cancer patient.

“I was shocked at the timescale that had passed, was passing, and was going to pass before I could get the treatment [on the NHS] that was going to help me,” he says. “I cannot believe that I had zero treatment throughout a three-and-a-half month period after being diagnosed. I was getting no treatment and then I went private and the treatment started in two weeks.”

After a successful career in retail which involved long days driving around the country from store to store, Colin had hoped to retire and spend more time travelling, playing golf, and seeing loved ones. But his reliance on employee private medical insurance means that, despite having cancer, he now feels he has to continue working.

“I don’t feel sorry for myself because it’s not productive,” he says over a matcha tea in an Edinburgh cafe, his drink of choice since his diagnosis. “But at 55, I had spent my entire career in food retail which is renowned for being long hours and people traditionally retire early. And yet now I’m in a position where I’m so reliant on private medical care. If I was to retire now without the private healthcare, my prognosis would not be as good because there are drugs that are not available on the NHS.”

One in eight men will get prostate cancer in their lifetime, but the risk doubles if a close relative such as a father or a brother has had the disease. Like all cancers, the earlier it is detected, the better. But Scotland has the worst late diagnosis rates in the UK, with more than a third of men diagnosed at stage four. That was the case for Chris Hoy, the six-time Olympic champion, who revealed last year that he has incurable prostate cancer, with a prognosis of between two and four years to live. Hoy, whose father and grandfather both had prostate cancer, was only diagnosed after visiting his doctor with shoulder pain. A scan found primary cancer in his prostate which had spread to his bones.

Last month Hoy and his wife Sarra were part of a meeting held at Bute House with First Minister John Swinney and health secretary Neil Gray to discuss the treatment of prostate cancer. Speaking afterwards, Swinney praised Hoy for showing “tremendous leadership”. “We know that the earlier cancer is diagnosed the easier it is to treat, and even cure, which is why the efforts of Sir Chris and others to raise awareness are so valuable,” the first minister said.

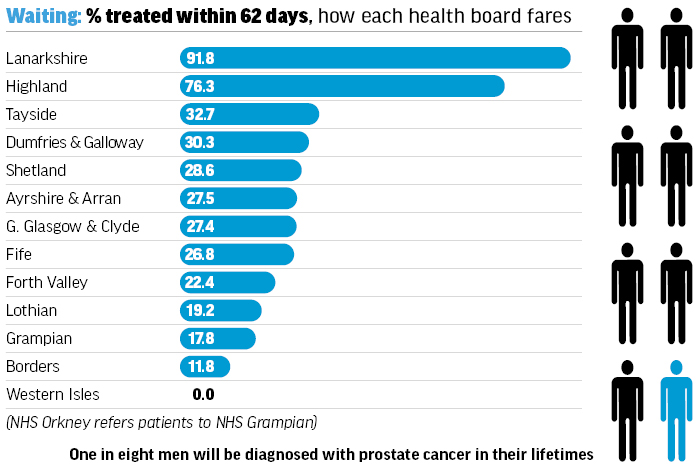

And yet statistics published by Public Health Scotland show the health service is currently failing men with prostate cancer, with not one NHS board meeting the government’s target that 95 per cent of patients begin treatment with 62 days of referral. In the first quarter of this year, just over a third of men began their treatment within the 62-day target. But that figure masks huge variations in the speed of treatment across the country, with the median wait just 52 days in NHS Lanarkshire compared to 143 days in NHS Grampian. In the latter health board, one patient waited 336 days to begin treatment, while in NHS Lothian another waited more than a year (393 days).

Chris Hoy launches Tour de 4 in Glasgow | Alamy

Chris Hoy launches Tour de 4 in Glasgow | Alamy

There are concerns too that GPs, the first point of contact most men will have with the NHS, are reluctant to carry out PSA tests due to outmoded ideas about the need for invasive biopsies to confirm the presence of cancer. Most patients with a raised PSA are now given an MRI scan as the first test.

Professor Alan McNeill, a consultant urological surgeon, helped establish the charity Prostate Scotland in 2006 after his father-in-law died of the disease aged just 57. He says it’s “far from unusual” that men with symptoms or who are worried about prostate cancer struggle to get a test.

“The prostate cancer support groups are filled with men, you’ll meet them everywhere, who say they tried to get a [PSA] test and couldn’t. It’s a big issue. Just last week in my clinic I had a man in his sixties who over the last two or three years has asked his GP four times and on the fourth time he got it. He had symptoms and his PSA turned out to be 24 – he’s almost certainly got a prostate cancer.”

McNeill, who is based at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh, says the system is “overwhelmed”, unable to meet the demand due to a failure of strategic planning on the part of the NHS and the government over the past 20 years.

“The situation we find ourselves in is that the incidence [of prostate cancer] has gone up as predicted but the capacity to meet the needs of these men is lacking. Maybe there is not messaging coming out saying to test these men who are at risk because everybody knows the system is struggling to meet the demand that exists. Sometimes there’s a sense we’re trying to protect the NHS from the overwhelming demand as opposed to ‘what does this guy in front of me need?’ The patient should be the focus.”

The prostate cancer support groups are filled with men, you’ll meet them everywhere, who say they tried to get a [PSA] test and couldn’t. It’s a big issue. (Prof Alan McNeill)

Ahead of Swinney’s roundtable at Bute House last month, the Scottish Government published updated referral guidelines for GPs in the hope of diagnosing more cancer cases earlier. For the first time, the guidelines included referral criteria for people with symptoms such as unexplained fatigue, nausea or weight loss which should, in theory, result in more patients being assessed earlier. But while welcoming the revised guidelines, Prostate Scotland said they still did not provide clear guidance for those without symptoms who are at heightened risk, such as those with a family history or men of Black African or Caribbean heritage, who are more likely to carry genetic mutations which increase the chance of developing the disease.

Screening

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men. Despite its prevalence (there were more than 5,000 new cases in Scotland in 2022, roughly the same as breast cancer) there is currently no screening programme, making it the most common cancer in the UK without one. While the NHS currently screens for breast, cervical and bowel cancer, the situation is more complicated when it comes to prostate cancer. That’s because even though it can spot the early signs, the PSA test is not a test for prostate cancer. PSA levels increase naturally as men age and there are other reasons why a reading may be high, such as inflammation, infection or benign enlargement of the prostate.

Despite the concerns, there are now those who believe the PSA test should be routinely offered to men who are at the highest risk, such as those with a close relative who has had the disease – men with two relatives who have had prostate cancer have a one in two chance of developing it. The UK National Screening Committee, which advises both UK and Scottish government ministers, does not currently recommend screening using the PSA test, citing concerns over its accuracy.

A review which had been due for completion last year is currently ongoing and is considering whether the benefits of screening would now outweigh potential harms. Charities Prostate Cancer UK and Prostate Cancer Research along with the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) all support some form of screening programme.

“We think the evidence is there to support at least targeted screening,” says Joe Woollcott, head of health policy, education and awareness at Prostate Cancer UK. “So that’s screening for men at the highest risk, such as men with a family history of the disease or black men.

Scottish men shouldn’t be having worse outcomes than men in other parts of the UK – it’s not right. (Chris Hoy)

“But we will be led by the evidence. Right now, the National Screening Committee are interrogating that evidence. If it’s a ‘no’ [to some form of screening] we will be bitterly disappointed but will look to what were the evidence gaps and how we can fill those.”

Last year Prostate Cancer UK announced the Transform trial, a £42m research programme which hopes to identify the best way to screen men for the disease. Developed in consultation with, and with the backing of, the NHS, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the UK Government, it will begin recruiting men later this year and will start by comparing four potential screening options, including fast MRI scans, genetic testing to identify men at high risk of prostate cancer, and PSA blood testing. It is hoped research will help inform the work of the National Screening Committee as well as creating a huge bio bank of samples, images and data to aid research into the disease.

Tour de 4

On a grey Sunday morning at the start of September, more than 5,000 cyclists gathered in Glasgow for Tour de 4, Hoy’s event designed to bring together cancer patients and their families while raising funds for potentially life-saving research. Inspired by the most famous cycling race of them all, the Tour de France, the event’s name is a reference to Hoy’s stage four diagnosis and his sense of defiance that he will not be defined by it. The event raised more than £2m for cancer charities.

One of Great Britain’s most decorated Olympians, Hoy is now sadly also a high-profile example of the threat posed by prostate cancer and the importance of screening for men with a family history of the disease. The 49-year-old received his terminal diagnosis in September 2023 after going to see his doctor about aches and pains that he thought were from working out in the gym. He had never been offered a PSA test, despite his father and grandfather both having had prostate cancer. Speaking about his diagnosis last year, Hoy said it had come “completely out of the blue”.

But in the months since he first spoke out, Hoy’s influence has been profound. Prostate Scotland reported a 69 per cent increase in visitors to its website in the weeks after the former cycling champion first gave newspaper and TV interviews about his cancer, while NHS data for England showed an additional 5,000 men had been given an urgent referral for urological cancers in the six months since Hoy spoke out. Hoy’s openness even convinced one of his personal friends to get checked out. The man was found to have cancer, but at an early, treatable stage.

“When I went public with my diagnosis, I didn’t think about the effect it would have,” he says. “It gives me hope that more men across Scotland are talking to each other about prostate cancer and checking their risk.”

Hoy’s outsized profile has made the Scottish Government sit up and take notice, writing to the UK National Screening Committee and hosting last month’s meeting at Bute House. But prostate cancer patients are still being diagnosed later in Scotland than in other parts of the UK. Hoy says that shouldn’t be happening.

“Scottish men shouldn’t be having worse outcomes than men in other parts of the UK – it’s not right,” he says. “I agree with Prostate Cancer UK that we urgently need an early detection programme, so that every man has a fair chance of getting an earlier diagnosis. In the meantime, I urge all men at risk to prioritise your health and get tested – even if you don’t have any symptoms.”

Despite Hoy’s own diagnosis, the survival rates of prostate cancer are generally good if caught soon enough. The risk of dying from prostate cancer fell by 7.8 per cent in Scotland in the decade to 2022, despite an increased incidence of the disease. But the speed of diagnosis is key. According to Cancer Research UK, almost all men diagnosed at stage one or stage two will survive their cancer for five years or more, as will 95 per cent of men diagnosed at stage three. However, for those diagnosed at stage four, that figure falls to 50 per cent.

And while just one in six men in London are diagnosed when too late to be cured, the figure in Scotland is more than one in three (35 per cent). Prostate Cancer UK, which did the analysis by comparing the proportion of stage four prostate cancer diagnoses in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland with the proportion of metastatic diagnoses in England, described the situation across the UK as a “postcode lottery”, saying the statistics for Scotland were “particularly shocking”. In contrast, only one in five men in Wales and Northern Ireland are diagnosed too late.

After Hoy spoke out about his diagnosis, Scotland’s health secretary, Neil Gray, wrote to the UK National Screening Committee, setting out the government’s support for its review of the case for prostate cancer screening.

“We will ensure we’re doing everything we possibly can to make sure we catch cancers earlier,” says Gray. “We do have an improving story to tell there in terms of cancer mortality in Scotland. We’ve got the risk of cancer mortality at a record low and that is because of the incredible interventions from a treatment perspective for those that have been diagnosed with cancer.”

Gray says the new referral guidelines will make it easier for asymptomatic patients to ask for a PSA test, but that it will remain a decision for doctors. However, he expects anyone who asks for a test to be given one.

“There are judgements to be made by our clinicians that it’s hard for a politician to be cutting across. But yes, I would expect the new referral guidelines [to make it easier] when we’re talking about the more at-risk groups of men, those over 45 from particular ethnic backgrounds and where there has been a family history...

“We’re also in discussion with the likes of the BMA and the Royal College [of General Practitioners] around how that process can be easier and more transparent for people and the conversations that GPs need to be having about the potential benefits and risks of the PSA test.”

Nearly 20 years on from the creation of Prostate Scotland, McNeill says men are better informed about the risks but still not getting the treatment they deserve.

“As a urologist and an advocate of men with prostate disease, it certainly feels like men aren’t being served as well as other parts of the community. A woman who has a breast lump will probably be seen and assessed in a breast clinic within two weeks.

“And the services for breast cancer seem brilliant. That has taken years to develop and probably came about because lots of young women died of breast cancer. We haven’t seen the same for men. A young guy with a family history who could potentially be cured if detected early isn’t getting as good a service as he might.”

Colin Pearse has remained upbeat despite his late diagnosis | Contributed

Colin Pearse has remained upbeat despite his late diagnosis | Contributed

Since beginning his treatment, currently a combination of a regular hormone injection and a hormone therapy drug, Colin has worked hard to remain upbeat, even writing his own guide on how to navigate your way through a terminal diagnosis.

“There was one day I heard a bird call and I thought to myself, ‘shit, I’m not going to hear that any more’ and then I was able to psychologically tell myself, ‘just embrace the fact that you can’ and when I hear it now, I’m excited to hear it.”

And despite his prognosis – he’s been told he likely has between five to seven years left – he says he remains determined to do everything he can to live for as long as he can.

“I’ve tried hard to equip myself with as much knowledge as I can to make a difference and to enjoy every single day,” he says. “I don’t believe in hope. I am absolutely determined to control all the controllables I can.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe