'Stroke care is very good if you give it a chance – but often it doesn’t have the resources'

Seventeen hours. That’s how long it took for Anthony Bundy to receive surgery for his stroke from the first 999 call. He died four days later, having never woken up following the thrombectomy procedure.

“Medically speaking it was successful. The blood clot was removed, and he had survived the operation. But he was still on life support and the damage had already been done by that time,” explains Anthony’s son, James Bundy, who for the last two years has been campaigning for a better service from stroke patients.

Anthony was a fit and healthy 53-year-old; he didn’t smoke, he didn’t drink a lot, and he had a good diet. He had in the months before his death set up his own business and was optimistic about the future. “All of that was taken away from him,” says his son.

When Bundy tells the story of how his dad died, it’s clear there were multiple failures that prevented the seriousness of his condition from being picked up and him not receiving the care he should have.

My mum, in the ambulance, was starting to make the calls for her family to get to Glasgow

Anthony had been at the opticians with his wife, Selena, when he collapsed one Sunday in June 2023. An ambulance was called but not immediately dispatched. His was an atypical presentation of stroke. “My dad’s face was not dropping, his speech was not slurred, and he could raise his arms. So, over the phone, they ruled out a stroke and an ambulance initially wasn’t dispatched,” Bundy explains.

“Clearly it wasn’t getting any better about 25 to 30 minutes later and it was called for again. They did a teleconference call, and it was clear that my dad was struggling to do it. He was struggling to take in information; his speech was much slower – but again not slurred – and the dizziness was there so trying to look at a screen and have a conversation was very difficult for him. But they eventually sent an ambulance.”

Anthony was taken to the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, but still no one suspected a stroke. He was left in the hospital corridor for five and a half hours, with the A&E “overwhelmed” with other patients. Only then did FAST symptoms begin to appear.

He was rushed to the stroke unit where a blood clot was confirmed and thrombolysis, an injection which aims to break up clots, was recommended. Unfortunately, the GRI only has this service available between the hours of 9am-5pm on weekdays. Anthony had to be moved to the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, only a short distance away but the journey still taking up precious minutes.

“My mum, in the ambulance, was starting to make the calls for her family to get to Glasgow. I met my family at the Queen Elizabeth, and there [dad] received thrombolysis but he was already on life support, unconscious. I never spoke to my dad again,” recalls Bundy.

Doctors told the family that Anthony required a thrombectomy, a surgery to physically remove the blood clot. But again, the lack of a 24-hour service meant he had to wait until the next morning for treatment. It took place at 9:30am on the Monday, but it was already too late. He was taken off life support on Thursday 29 June.

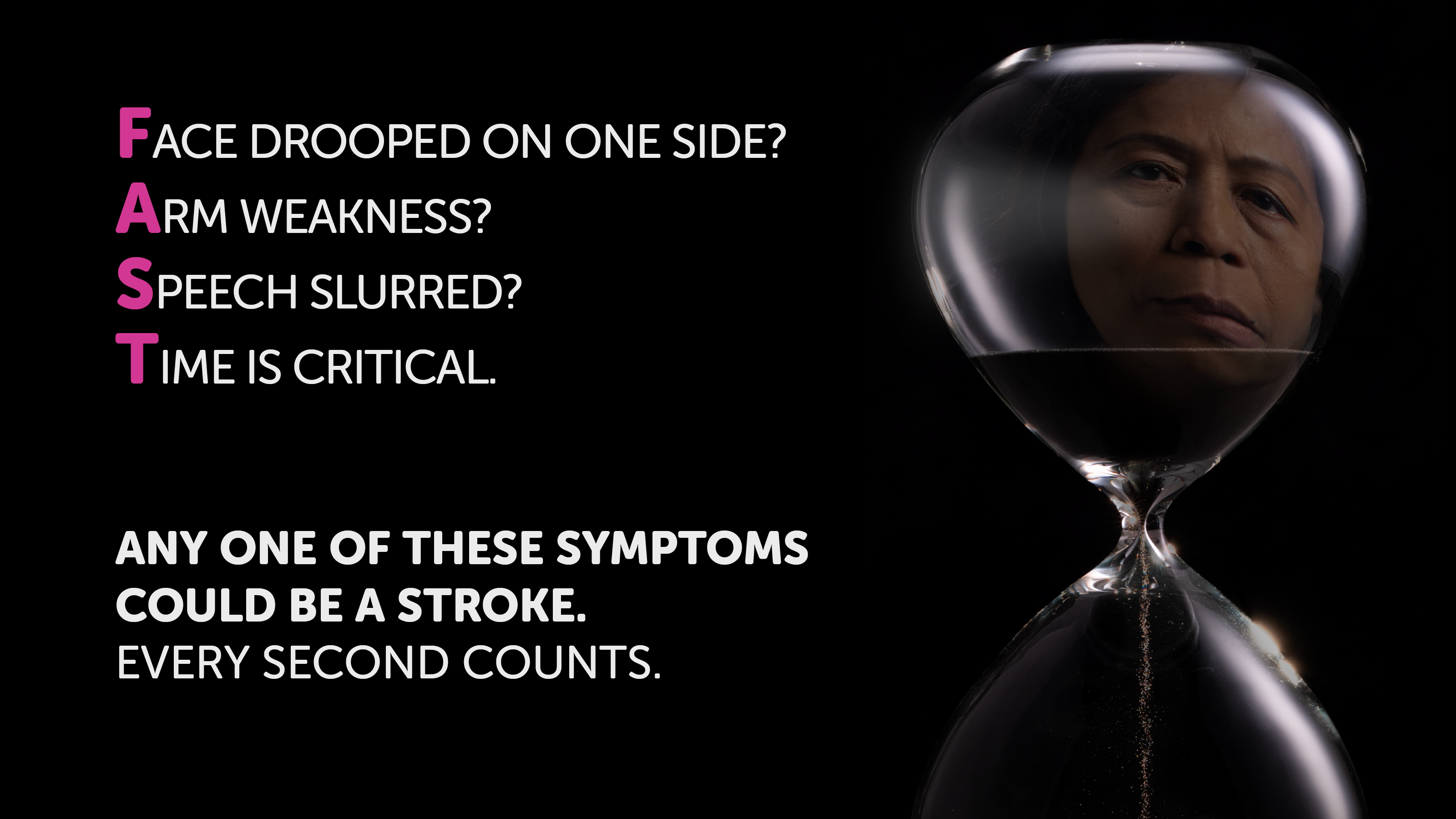

Act FAST

In the years since Anthony’s death, Bundy has been campaigning to improve awareness of the symptoms of stroke beyond the big three of face, arms and speech. He believes that changing the FAST acronym to BE-FAST – inclusive of balance and eyes (a loss of focus) – would lead to better public awareness both among the public and within the medical profession.

In September 2023, Bundy, who is a Scottish Conservative councillor in Falkirk and previously worked for Tory MSP Stephen Kerr, lodged a petition with the parliament seeking a review of FAST. While accepting that a drooping face, inability to raise both arms and slurred speech are more common indicators, he is concerned that these symptoms have become the main test and others are being overlooked – particularly when emergency departments are “under too much pressure”, essentially forcing staff to rely on “the basics rather than going to that next level”.

“That’s why we should expand to BE-FAST, be a bit more informative [for the public]. If they’re taught BE-FAST rather than FAST, they’re going to capture more strokes,” Bundy argues. “It’s better to get the scan, find out it’s not a stroke, compared to what happened with my dad. It’s better to be more inclusive and have that risk of false positives than it is to be so narrow where people are losing their life.”

But stroke charities and the Scottish Government have disputed this. Public health minister Jenni Minto, in a letter to the parliament’s petitions committee earlier this year, said there was “insufficient evidence to support replacing FAST with BE-FAST”. And John Watson, associate director for the Stroke Association in Scotland, warned that doing so might actually do more harm than good. That’s because it would push more people into already under-resourced stroke units, which would end up preventing people who are having a stroke from being seen as quickly.

FAST works, Watson says, because the three symptoms are “indicative of a stroke, but are not really indicative of anything else”. “That makes FAST a very good initial triaging question. The best thing to do is divert them onto the stroke care pathway and that means going to a stroke unit, being seen by a stroke clinic, getting a brain scan, getting into a stroke ward.”

If a system is under that kind of pressure, any system, no matter how good it is, it’s going to fail people

Where Watson and the Bundy family agree is that there is too much pressure on A&E departments generally, which means people are being failed because healthcare staff are unable to spend enough time with patients. That’s been borne out in figures published by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine last month, which estimated there were over 800 excess deaths due to long A&E waits in 2024.

Watson says the Bundys were “let down by the system”. “After Anthony Bundy wasn’t showing FAST symptoms, nobody spent time with him trying to figure out what was going on. He was left for hours. I’ve spoken to people working in emergency departments about this and how they use this, and in theory they should be looking beyond FAST; FAST is an initial test but they should be having in mind other things. But they need the time and the capacity to be able to sit with somebody and figure that out because it’s not obvious what’s going on.

“And the problem is that when you have emergency departments working at double capacity, they’re dealing with twice as many people as they’re resourced to do, those people cannot get the care that they’re supposed to get. I spoke to one emergency department physician who said to me, look, if a system is under that kind of pressure, any system, no matter how good it is, it’s going to fail people because it’s overloaded.

“But the answer to that is not to send lots more people to the stroke team because they are not set up to deal with that. They’re less well-equipped to deal with it than the emergency department are.”

24/7

The delays in treatment experienced by Anthony Bundy are sadly not uncommon. Recent figures published by Public Health Scotland (PHS) show a record of failure for stoke patients. Scottish ministers were accused this summer of having “failed stroke survivors” after a series of targets were missed for the seventh year in a row.

Last year, almost half of patients did not receive the inpatient bundle – care that includes brain imaging, aspirin, swallow screening and rapid admission to a stroke unit. It is the latter two that are causing the biggest problem, with only two-thirds of patients receiving a swallow screening within four hours (unchanged from 2023) and three in ten not being admitted to a specialist ward within a day (slightly improved from 2023).

Currently there is extremely limited treatment at weekends and no access to treatment overnight anywhere in Scotland

“The stroke unit admission standard remains very challenging,” the PHS report says. “Much of the poor performance reflects larger issues with hospital flow but is also a marker that stroke is, perhaps, not given the same priority as other specialties within our hospitals.”

This, too, is believed to be behind the poor performance on thrombolysis and thrombectomy. There is no national clinical standard for the proportion of patients receiving thrombolysis, but there is an expectation that among those that do, door-to-needle (DTN) time should be within 30 minutes for half of patients, and within an hour for 80 per cent of patients. Yet in 2024, no health board was close to meeting either target. Worryingly, due to a lack of a 24-hour service “different hospitals have significantly different DTN times in and out of hours,” the report says.

Thrombectomy performance is even worse, with only 2.2 per cent of stroke patients undergoing this surgery in 2024. Performance in Scotland compares poorly to England, where 3.9 per cent of stroke patients got a thrombectomy in 2023/24. Not everyone is a suitable candidate, but research estimates between 10 and 15 per cent of stroke patients should receive one. No part of the UK is close to meeting that.

In part, the low numbers of people getting a thrombectomy in Scotland is because facilities are extremely limited. Only three hospitals are able to carry out the procedure – Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, and Ninewells Hospital in Dundee – and none of them are 24-hour services.

“Most of the population of Scotland now has access to thrombectomy at some time during the week. However, there are still significant periods of time when people are not able to get treatment,” the PHS report confirms. “This is the most significant issue leading to lower treatment rates than we should be delivering and means the current access is very inequitable. Currently there is extremely limited treatment at weekends and no access to treatment overnight anywhere in Scotland.”

The report goes on to highlight that a lack of appropriately trained staff, the small number of operating suites, limited financial resources, and the competing priorities of health teams involved all contribute towards this.

Graham McGowan was a keen walker before his stroke in 2022

Graham McGowan was a keen walker before his stroke in 2022

Graham McGowan was one patient who missed out on a thrombectomy because of the time of day he had a stroke. He’s been left with a life-altering disability that might have been avoided.

“I don’t want to dwell too much on the ‘what ifs’ and the cost of me not getting a thrombectomy, as it doesn’t help me mentally,” he says. “But if you take me as an example, I was working and had an active, healthy lifestyle before I had a stroke. Now, I can’t live independently. I can’t work. I can’t drive, ski, run or mountain bike. My wife is now also my carer and there has been a dramatic change in our circumstances.”

McGowan, who lives in Aboyne, was rushed to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary in May 2022. A brain scan revealed a blood clot, and doctors advised he should receive a thrombectomy. But it was 9pm in the evening and the nearest specialist hub, Ninewells in Dundee, does not perform thrombectomy after 7pm. Instead, Graham was given thrombolysis, and has been left with paralysis down one side of his body.

His story is unusual, in that most stroke survivors who don’t receive a thrombectomy don’t know whether it would have made a difference. Stroke doctors are understandably reluctant to tell patients they should be treated with thrombectomy but can’t be because of limited availability. Yet with rates so low, doctors and stroke charities believe many hundreds of people must be missing out.

You save a lot of money, you get the system working more efficiently. It’s exactly the kind of change that you need

The Scottish Government has previously committed to providing a 24/7 thrombectomy service. The stroke improvement plan published in 2022 set out an aim to have “24/7 availability across Scotland by 2023”. But with that deadline having come and gone, campaigners are concerned the ambition has fallen by the wayside. Minto has said the government “remains committed to implementing a high quality, clinically safe and equitable thrombectomy service”.

The lack of capacity within stroke care not only comes at great cost to the patients, but it’s also expensive for the NHS. Research suggests that thrombectomy saves the health and care system around £47,000 per patient over five years because the cost of ongoing care is reduced. Watson argues getting stroke care right is therefore not only good for patients, but beneficial to the wider NHS too.

He says: “We hear a lot about reform to the NHS to enable it to deal with the demands that are put on it. This is what those kind of reforms look like. It’s getting a system whereby you treat somebody quickly, they spend less time in hospital… and they leave hospital with less in the way of ongoing support needs. You save a lot of money, you get the system working more efficiently. It’s exactly the kind of change that you need when you’re under pressure. But the fact that they’re under pressure gets in the way of making the change. That’s really, really frustrating.”

Stroke remains one of the leading causes of death in Scotland, alongside heart disease, cancer and dementia. But death from stroke has decrease by 12.7 per in the last decade, even while incidence rates have been stable. That’s attributed to medical improvements.

Watson suggests these relatively new advances are part of the reason stroke is not yet being prioritised. “The system is yet to catch up with the fact that there’s a lot we can do,” he says. “Our general view on stroke care is that it’s now very good if you give it a chance to be good, but often it doesn’t have the resources. It doesn’t have the place within the hospital planning system. It doesn’t have the place at the top table when the hospital-wide planning decisions are getting made.”

Long-term care

Beyond emergency care, access to rehabilitation is crucial for reducing survivors’ long-term support needs. Stroke is a leading cause of disability and while much of that is related to how fast someone gets emergency treatment, proper aftercare also has a role.

Clinical guidelines currently recommend survivors get at least three hours a day, five days a week. That can come from a range of sources, depending on what a patient needs – from speech and language therapy to orthotics to psychology and more. However, there is little in the way of data to show how many people are receiving the recommended amount.

We should be providing a seven-day day service, but most of the health boards are providing five-day

Watson says: “Some people get really good rehabilitation; some people don’t… We don’t know how much people actually get because rehabilitation figures are not included in the stroke care audit. The stroke care audit is going to expand to include some key rehab numbers, but we hear from all across the country that’s not what people are getting. There’s a big gap in terms of rehab provision.”

On the bright side, the importance of access to rehab has been increasingly recognised in recent years, according to stroke consultant Gillian Capriotti.

Capriotti, who chairs the Scottish Stroke Allied Health Professional Forum, praises experts in the field and the voices of those with lived experience for this change. “It has become much more of a focus within the publications and the national guidelines as well,” she says, “and that’s allowed us to make sure that we’re addressing gaps and have clear pathways for people with different levels of disability and different areas of disability, to make sure that there’s a consistency of approach, a level of quality and that people are receiving the same high standards of rehabilitation in areas across the country.”

But proper resourcing is a barrier to delivery. Capriotti suggests when it comes to funding, “the conversation tends to have got stuck” at providing emergency care. “The papers and the plans and the programmes are all very much advocating that stroke rehab is important and we need to have therapies and resources to support that, but in reality the funding isn’t really there to enable that just now.”

Staffing, too, is a problem across the allied health professions who lead on rehab. Capriotti says across Scotland staffing levels are “pretty far away” from what is required. “We should be providing a seven-day day service, but most of the health boards are providing five-day. In some areas they’ve been able to increase that but it’s not consistent and if we want to be able to provide that level of rehabilitation to allow patients to move, to get home quicker, and to be able to keep the throughput going and continue to drive that forward and get people better, we do need to invest in seven-day working, which is not something we’re doing.”

She adds that efforts are underway to make stroke care a more attractive career path, such as the creation of senior positions to enable progression without needing to change clinical area of expertise. But she says it’s also important to consider what care does need to be delivered by AHPs and what can be delivered by others, such as healthcare support workers, community workers or the third sector.

Stroke rehabilitation can take many different forms | Alamy

Stroke rehabilitation can take many different forms | Alamy

Professor Lorna Paul, an expert in allied health science at Glasgow Caledonian University, is taking forward a feasibility study in this area – looking at whether telerehabilitation could help deliver more community-based options. Paul explains: “With the best will in the world, even if you see the community team twice or three times a week, you might see them for an hour at a time. But what are you doing for the rest of the time? The premise of this study really is how can we support patients to do three hours of therapy, what we call self-management, without a therapist looking over the top of you to see to see what you’re doing.”

She’s working with the health boards in Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Forth Valley, and Tayside to test out how a telerehab platform might work, with the aim to later do a UK-wide study which would look at clinical outcomes and cost savings. The idea is that by supporting some patients via telerehab, clinicians’ time will be freed up to deal with more complex cases.

Responding to all these issues is becoming ever-more pressing as cases of stroke are predicted to rise significantly over the next two decades. The Scottish Burden of Disease study has projected a 35 per cent increase in cerebrovascular disease between now and 2044. Without intervention, this is “likely to impact on the sustainability of services in the future,” it warns.

But, it adds, this is “not inevitable – effective prevention at all levels can contribute to reducing the number of people having a stroke and assist those who have had a stroke to live at lower levels of severity”.

It’s a point echoed by Watson. “We always say there’s three elements to it: stroke is preventable, stroke is treatable, and stroke is recoverable. I always put all of these things down as prevention… Preventing somebody having a stroke is great. If you treat somebody quickly, you prevent damage from happening to their brain. But also, if you then get the right rehabilitation, you prevent whatever damage has happened from being the norm from there on.”

Back in Falkirk, Bundy is determined to keep pushing for change so that fewer people die like his dad. “If his death means that hundreds of thousands of Scots lives are saved in the future, then… well, I’m not saying it would have been worth it, but his life would have more of a legacy than it has now.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe