Irvine Welsh: It's the centrists who are the villains

Perhaps the biggest surprise in Irvine Welsh’s new book, Men in Love, is the author’s note which comes at the end, a sort of postscript in political correctness which reminds readers that the novel they’ve just read is set in the 1980s and therefore contains words or themes modern audiences may consider “discriminatory or offensive”. For a writer who shot straight into the literary firmament with his 1993 debut Trainspotting, an unflinching portrayal of heroin addiction in 80s Edinburgh, and who has never shied away from challenging or unsettling his readers, it feels like quite a departure.

And yet in the three decades since the publication of Welsh’s most famous novel and its subsequent screen adaptation, the growth of the internet and in particular the rise of social media has created a culture that can throttle interesting and unusual voices and cause some writers to opt for self-censorship. You need only look at attempts to shut down debate at last month’s Edinburgh festivals. During the Fringe, Summerhall said it had been an “oversight” to host a talk involving Scotland’s deputy first minister, Kate Forbes, due to her views on gender. And the Edinburgh International Book Festival was criticised for its decision not to platform so-called gender-critical voices, including authors of The Women Who Wouldn’t Wheesht, an essay collection which has become a bestseller.

That’s not to say Welsh has gone woke. His fifth Trainspotting spin-off so far, Men in Love is the closest to the original in chronology, picking up in the immediate aftermath of the drug deal in which Mark Renton screws over his friends and accomplices, Begbie, Sick Boy and Spud. The narrative flits between the four main characters, with Renton having fled to Amsterdam and Sick Boy attempting to swap Leith’s Banana Flats for aristocratic London as he marries the daughter of a senior civil servant in Margaret Thatcher’s government. For a novel ostensibly about love and where many of the chapters begin with quotes from Romantic poets such as Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Welsh still retains the power to shock, notably in a scene depicting the making of a porn film. In another, Jimmy Savile is introduced as an incidental character as he picks up his knighthood at Buckingham Palace.

Welsh is coming to the end of a busy round of interviews publicising both his novel and a well-received film about his life, Reality Is Not Enough, when we meet at the Edinburgh Futures Institute, the book festival’s home since last year. He seems tired but never ducks a question, giving typically forthright answers on everything from Scottish independence to the ongoing spat between JK Rowling and former first minister Nicola Sturgeon. At 66, he is now an elder statesman of Scottish letters and yet undeniably still the country’s best-known literary novelist. But despite selling over a million copies in the 90s, he thinks his most famous work would struggle to find a publisher today.

“It wouldn’t get published now,” he says of Trainspotting. “I think you need to concentrate quite hard in the first 30 pages before the rhythms establish [because of] the language it’s written in. I don’t think publishers would believe that readers could do that and it would just be seen as too high-risk. Publishers used to love high-risk books, but now everything has to be like something else.”

Welsh is quick to disavow the author’s note at the end of Men in Love, an addendum he says was his publisher’s idea and something he went along with for the sake of a quiet life.

“Back in the day, publishers encouraged you to be as controversial as possible – now they don’t,” he says. “It’s something they get nervous about, but it makes no difference to me whatsoever. It’s pandering to a dumbing down, it’s kind of patronising readers in a way. Then again, nowadays in the internet age somebody will pull a quote from a character out of one of the books and they attribute it to the author, which is a horrendous thing – I hate when that happens.

“The whole idea about creating characters is that you’re creating characters outside of yourself. It’s fiction and that should explain and contextualise the whole thing. Just having that note there [at the end of the book] saved me going through every single thing. It’s a catch-all, but then the catch-all should be that it’s fiction set in the 80s.”

Irvine Welsh photographed for Holyrood by David Anderson

Irvine Welsh photographed for Holyrood by David Anderson

Born in 1958, Welsh grew up in Muirhouse, north Edinburgh, the son of a waitress and a Leith docker. After time spent living in London where he played in punk band The Pubic Lice, he moved back to Edinburgh, working in the council’s housing department and studying for an MBA at Heriot-Watt University. At the same time he was spending his formative years in Muirhouse, an area of the capital which later became synonymous with the HIV/Aids crisis of the 1980s, my mother’s family – surname Begbie – was living in nearby Drylaw, some of them attending the same high school as Welsh. It’s always been a matter of fascination in our family whether my mum and her sisters, all of whom led successful, law-abiding lives, were somehow the inspiration for the psychopathic Francis Begbie, the character memorably played by Robert Carlyle in Danny Boyle’s 1996 film version of Trainspotting.

When I ask Welsh about this, his eyes light up. But while he remembers a Begbie family living nearby, he says the inspiration was more likely the photographer Thomas Begbie (another distant relative) whose sepia images of nineteenth century Edinburgh were the subject of a major exhibition at the City Art Centre in 1990.

Things like Gaza are showing people what we’ve been supporting all these years… The villains are not the oft-demonised easy targets of the far left or the far right, it’s been the centrists that are the villains.

One of the enduring creations of Scottish fiction, Begbie features heavily in Men in Love. Violent, misogynistic and homophobic, at one point he is dissuaded from hitting on a bridesmaid at Sick Boy’s wedding by being misled into thinking she is a “post-operative transsexual”. It’s the sort of episode a skittish publisher might balk at and perhaps at least part of the reason the author’s note was inserted. Indeed, the issue of gender was once again to the fore during this year’s book festival with the publication of Sturgeon’s memoir, Frankly, and her admission that she should have “paused” controversial attempts to reform the Gender Recognition Act while she was first minister.

Following the publication of Sturgeon’s book last month, author JK Rowling posted an almost 3,000-word review, variously describing the former SNP leader as “Trumpian” and someone whose gender beliefs had created a “dystopian nightmare” for Scottish women. In language more likely to be found in the pages of Welsh’s novels than in Harry Potter, Rowling added that Sturgeon had been made to look like a “fuckwit” during the row over Isla Bryson, the double rapist who was briefly housed in a women’s prison before being moved to the male estate.

“If you look at these two women and the vitriolic abuse they receive from men, that’s something they’ve got in common,” Welsh says “To me, that’s the thing they both should be rallying around but if I say that I’m mansplaining. These are women’s issues, these are trans people’s issues – you don’t want white, straight guys pontificating about all this; let women and trans people sort it out for themselves.”

Welsh has described Sturgeon’s attempted gender reforms as “social engineering”, and while he says they were part of a “laudable” attempt to create a more progressive society, he believes they have helped alienate voters and undermine the cause of Scottish independence.

“If you’re trying to say things like biology doesn’t exist, that is not people’s perceived reality. If you do that you just lose people or you make them very hostile and against the whole thing you’re trying to advance; it becomes counterproductive. That’s where all the far-right people come in and say, ‘we get you, fuck those liberals’. People will embrace that because they’d rather be told they’re valued. It’s like the Hillary Clinton ‘basket of deplorables’ thing – if you tell people they are pieces of shit, they’re going to go ‘fuck you’ and go somewhere they’re going to get sustenance.”

Welsh believes Sturgeon is a “better, more human” kind of politician, but he disagrees with her characterisation of those who opposed her gender reforms. Making her own appearance at the book festival earlier in the month, the former first minister told Kirsty Wark the issue had been “hijacked” by transphobes, adding that while she didn’t believe everyone who opposed the now-abandoned legislation was transphobic or homophobic, many were, something she called the “soft underbelly of prejudice”.

“It’s like saying that everyone who believes in trans rights is some kind of gender fascist who follows the line right down to the Paedophile Information Exchange,” Welsh says. “You get these extreme ideas and extreme theories that both sides will advance in the bear pit of social media, and it has that polarising effect.” He says that if you ask most people in the street, they’ll be in favour of women’s rights and trans rights, although he doesn’t expand on how the two can happily co-exist.

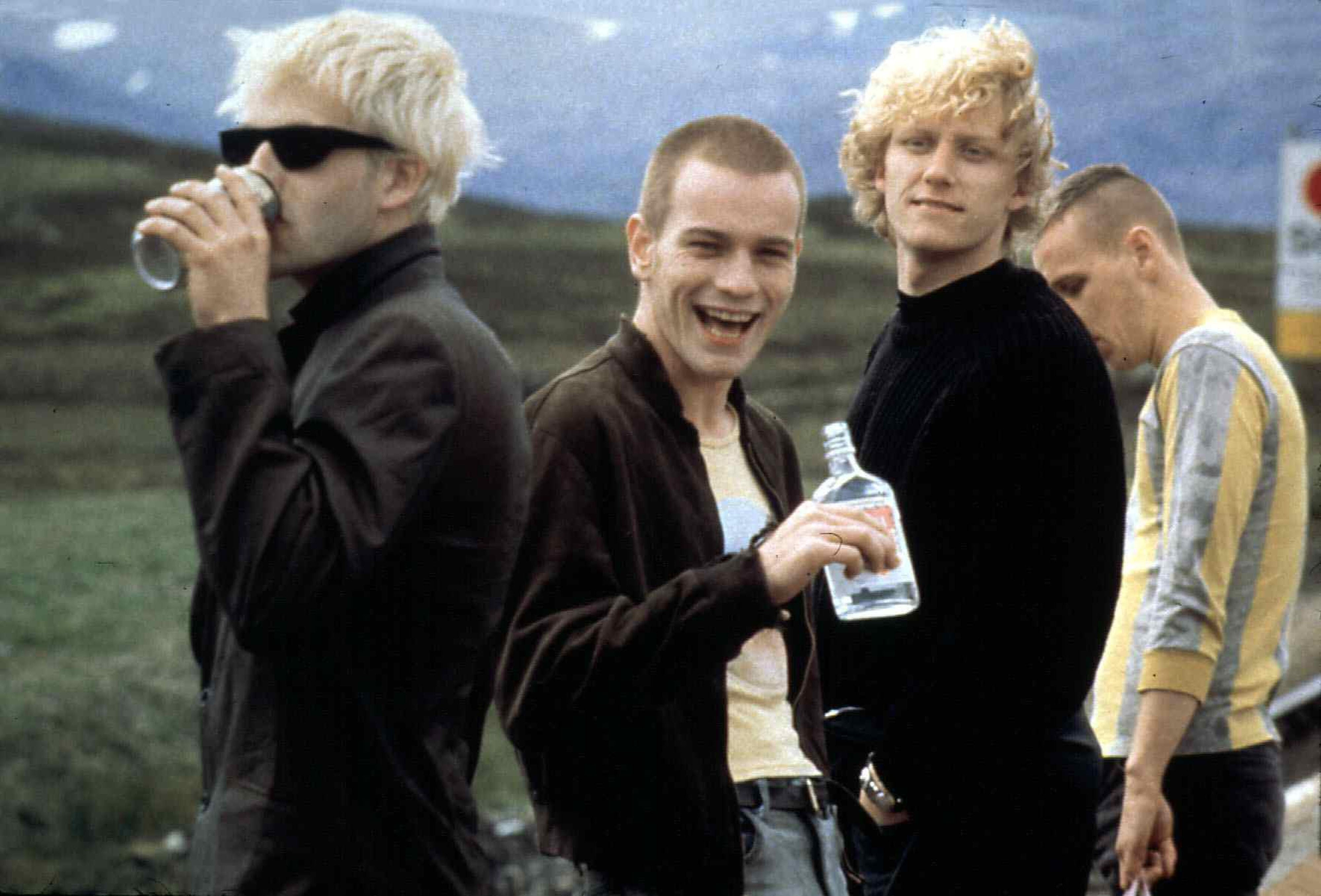

Danny Boyle's Trainspotting will celebrate its 30-year anniversary next year | United Archives / Alamy

Danny Boyle's Trainspotting will celebrate its 30-year anniversary next year | United Archives / Alamy

Welsh first began publishing short pieces of work in 1991, appearing in the West Coast Magazine, New Writing Scotland and the influential literary magazine Rebel Inc, which was set up by former Scottish Socialist Party candidate Kevin Williamson with the motto ‘Fuck the Mainstream!’. Rebel Inc would also publish writers such as Laura Hird and Alan Warner, whose novel Morvern Callar became a 2002 movie directed by Lynne Ramsay. But it was with the publication of Trainspotting in 1993 that Welsh was catapulted to literary celebrity. Set in the dark days of the mid-1980s, the novel nevertheless captured the imagination of the early 1990s, its status further enhanced by Boyle’s film which featured a soundtrack of Britpop artists such as Blur and Pulp.

Welsh followed it up with a collection of short stories, The Acid House (1994), and the deeply unsettling Marabou Stork Nightmares (1995). To date, he has written a further four novels featuring the Trainspotting characters: Porno, Dead Man’s Trousers, Skagboys and now Men in Love. That he continues to loom large over Scottish literature more than 30 years on from his debut is both testament to his own longevity but also the absence of young writers – particularly young male writers – coming through to take his place.

“It’s very concerning,” Welsh says. “When you look at all the great Scottish writers that I looked up to – Alasdair Gray, James Kelman, Janice Galloway and William McIlvanney – just about every one of them lived in a council house. Whereas the great English writers that were their equivalents – Martin Amis, Ian McEwan, Julian Barnes – they’re all fabulous writers but they all had that Oxbridge, upper-middle class background.

“That was the great thing about Scotland – we had a sense that people who came from marginalised or relatively dispossessed communities could write about that, and it was seen as being right in the mainstream of our culture. Now our culture is corporate – it’s corporations that say this is what you are going to read, this is what you’re going to watch.”

In his latest novel, Welsh’s characters are primarily working-class men living on the fringes of society, cast adrift in the era of deindustrialisation under Thatcher. He sees parallels between what happened then and what’s happening now.

“We’re drifting back into this thing where young men, in particular, are confused and disempowered,” he says. “They’re not reading, so if you’re not reading, you’re not writing. You’re not producing a lot of writers. What you are producing is wankers who are spending a lot of time wanking to porn online. We need to get people reading and then we’ll have people starting to write about their own experiences.”

Welsh was among the high-profile Scots from the world of arts and culture who spoke out in favour of independence in the run-up to the 2014 referendum. In an article written for Bella Caledonia the year before the vote, he said being part of the UK had “foisted 35 years of a destructive neo-liberalism” on Scotland and “prevented us from becoming the European social democracy we are politically inclined to be”. Ridding ourselves of the “imperialist baggage” of the British state would lead to a flourishing of new possibilities, he said. “The idea of the political independence of England and Scotland leading to conflict, hatred and distrust is the mindset of opportunistic status-quo fearmongers and gloomy nationalist fantasists stuck in a Bannockburn-Culloden timewarp, and deeply insulting to the people of both countries,” he wrote.

But much has happened in the decade since: Brexit, the election of Donald Trump in the United States and the rise of the far-right across much of Europe, the UK included. While expectations surrounding the election of Keir Starmer as prime minister last summer were low, the Labour Party has nevertheless failed to lift the national mood, hamstrung by its own missteps and the deep unhappiness left behind by 14 years of Tory rule.

Like many others, Welsh, who splits his time between Edinburgh, London and Miami, seems more pessimistic now about the power of politics to change lives for the better and talks about moving into a “post-culture society” where the internet and the power of big tech increasingly control our lives.

“Things like Gaza are showing people what we’ve been supporting all these years… The villains are not the oft-demonised easy targets of the far left or the far right, it’s been the centrists that are the villains. They’ve been presiding over this military/industrial complex and this warfare state.

“It’s not just about Scottish independence; it’s about an imperialist nation state that no longer serves the purpose of its people and it’s crumbling. Why do we have a monarchy, a House of Lords, and an aristocracy? These things aren’t adding value to people’s lives, they’re sucking the resources out and ruining opportunities for people. I want to see the best form of government, the most decentralised and local form of government that empowers people and involves them – English independence, independence for the north of England or regions of England, Cornish independence, Welsh independence… These for me are important because they put power back into a community.”

Despite moving through a period between 1987 and 1990 (it obliquely references the Lockerbie bombing and the Tiananmen Square massacre), Welsh says Men in Love is a reaction to what he calls our modern “anti-love” world. The book begins with the character Eddie Reece, a sailor returned from sea to the drinking dens of Leith. In the style of Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Reece has wisdom to impart from his travels, telling Renton and Sick Boy to ‘think global’ when it comes to women. You can be a ‘lover’ or a ‘shagger’ but not both and beware: ‘when a shagger faws in love, it’s game over. Always spells trouble…’

Welsh has found love himself again recently, marrying his third wife Emma Currie (to whom his latest novel is dedicated) in 2022. Appearing on the BBC’s Take Four Books podcast last month, he spoke of how love is the “barometer of emotional health” before picking Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time and James Joyce’s Ulysses as influences on his work. But it would be a mistake to think the author of such disturbing works as Filth and Marabou Stork Nightmares had somehow mellowed; Men in Love retains much of the sex, violence and drug-taking which punctuate Welsh’s earlier works.

The novel unfolds against the background of what became known as the Second Summer of Love, when acid house helped fuel rave culture and the giant outdoor gatherings that inevitably led to a moral panic among Britain’s tabloids. Re-located to the Netherlands after ripping off his mates, at one point in the novel Renton takes ecstasy in an Amsterdam night club: ‘Ah feel like ah belong here experiencing a deep connection to these people I barely ken. Whatever happens in life, we’ll always be friends’.

Welsh being interviewed at the Edinburgh Futures Institute | David Anderson

Welsh being interviewed at the Edinburgh Futures Institute | David Anderson

Welsh says it’s these sorts of communal experiences we crave as humans, but which are getting rarer as society becomes more atomised and online due to the ubiquity of the mobile phone and our apparent unwillingness to engage with those outside of our immediate social circles. For him, that helps explain some of the euphoria felt by those attending Oasis’ Edinburgh concerts over the summer, despite £400 tickets being massively at odds with the DIY spirit of the early 90s rave scene.

“We’re moving into a post-culture society now,” he says. “The internet basically just gives us instructions – it used to be something that was a library that we went into to explore but now it’s all been enclosed by the tech giants and they’re basically milking us and selling reduced versions of ourselves back at us. We’re there just to take instructions and provide data.

“Our mental health is being wrecked by the addiction of the mobile phone and the dopamine hits [it provides]. We’re being reduced into a bubble where we’re not really interacting with one another in the street. You saw it with the Oasis concerts and Taylor Swift at Murrayfield, people just wanting to come out and be together – and that’s a reaction against all the shit that we have to deal with.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe