Data in the dirt: How tech is transforming Scottish farming

Rotors whirring above a field, a dark shape flies slowly along, scanning the ground. It hangs for a moment in one spot, lowers slightly and sprays a liquid onto the green field below before moving off into the distance.

So, what just happened?

A drone, a specially designed model that can release chemicals from its rotor arms, is spraying fertiliser onto a patch of field that needs it before flying back to its operator. A markedly different approach to covering an entire field with fertiliser in the hopes of hitting a spot that needs extra help.

These drones, which are already widely used around the world, are just one of the many high-tech gadgets that Scottish farmers are utilising as agricultural technology becomes a larger part of their toolbox. From driverless tractors to cows wearing health trackers, the advancement of technology and artificial intelligence could change the look of farming in Scotland forever.

James Braid is one of the first people to offer agricultural drone technology in Scotland, through his company SkyPin Drones. He is licensed to fly a range of drones and uses them to help farmers survey their land, distribute chemicals and sow seeds using sophisticated cameras and spraying systems.

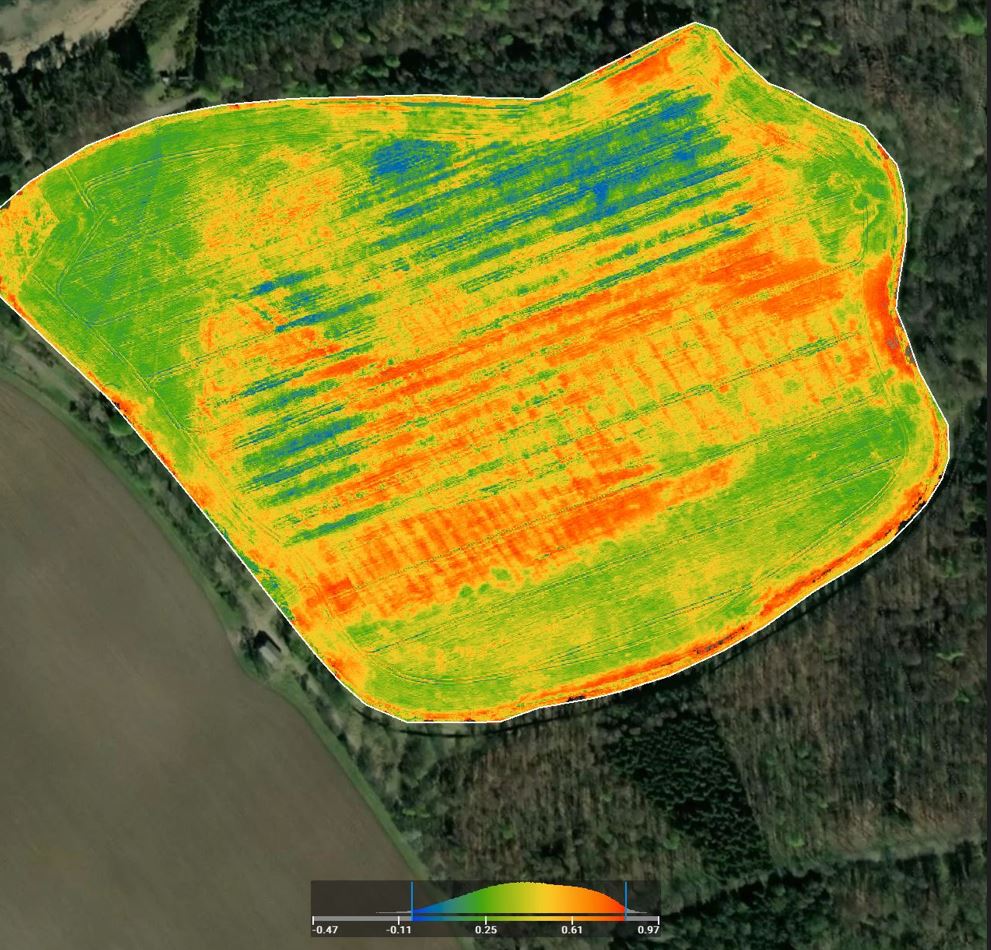

“The drone has a camera that picks up the reflectance of light waves from plants,” Braid explains. “This reflectance comes from a plant when it sucks in some wavelengths of light and reflects others it doesn’t need. This highlights where the crop is growing healthily, where it’s having problems and, in some cases, where it’s not growing at all.”

This tech means that Braid can spot the difference between two identical-looking plants through the light that they reflect back into the camera. The difference shows up clearly when inputted into a dedicated software system that produces a detailed colour-coded image of the field, showing spots that may need extra attention. Once a problem patch is identified, the drone can fly over it, spray the specific area and return, all in a matter of minutes.

The cameras also collect a large amount of additional data for farmers, as they survey the land below and produce maps that can highlight details down to individual blades of grass in a field. This allows farmers to gain a granular understanding of the makeup of their farm, shining a light on areas that could be missed from ground level.

Using these maps, farmers can predict water run-off patterns for heavy rains, see where weeds are infiltrating a field and even survey the number of deer on their land. Braid says that this approach can cut down on the amount of chemicals deployed onto fields around Scotland, while also reducing costs for farmers as a by-product.

“By applying chemical products more effectively and efficiently, I think farmers will see a big cost saving,” says Braid. “But I think that accurate data collection is very, very important as well. These drones can capture a load of data, but it’s useless if a farmer can’t use it effectively or cost-effectively. So I think the way forward is that you’re going to see AI start to get involved.”

By utilising agritech like drones and increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence platforms, farmers are finding ways to adapt in a sector that has faced significant challenges over the last year. According to the Scottish Government’s Scottish Farm Business Survey, individual farm business income experienced a decline of over 50 per cent in 2023-24 from the previous year.

These figures are variable year-on-year and can be affected by things such as poor weather conditions and feed prices, but the decline is an indicator of the pressure that farmers are under as margins grow tighter and costs increase.

Despite these statistics, there are opportunities for growth as the technology and methods for mitigating risk and maximising productivity on farms continuously evolve, utilising the latest innovations from around the world.

In China, the number of drones engaged in agricultural practices is estimated to be over 500,000. These drones are authorised to spray pesticides and transport crops, something UK-based operators are not allowed to do under current regulations that prohibit the airborne distribution of potentially hazardous materials.

“Fundamentally, a lot of farming practices are the same as they always have been,” says Eileen Wall, a professor in integrative livestock genetics and head of research at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC). “But what we’ve seen over the last decade is a rapid advancement of tools that are available to help real-time decision support for farmers.”

That real-time decision support for farmers can come in a mixture of forms, but at the SRUC, Wall is focusing her research on developing techniques to gather in-depth information about the genomic and genetic makeup of a farm’s animals. “The work I do focuses on genetics and genomics and there has been a massive change in that in the past five or so years, where rather than just using classical pedigree information we’re using genomic information and AI to create new traits,” explains Wall. “So, we’re looking at AI to predict bovine TB status, pregnancy status, et cetera. Then we can integrate that with genomic information to help farmers breed animals that are suitable for their production system.”

By using these systems to gather in-depth information on a herd of cattle, for example, Wall’s methods can alert farmers to specific animals that may be more suitable for breeding to create a healthier and more profitable end product. As more data is collected, farmers can also start to spot the signs of disease and illness without having to call a vet out to inspect each individual animal.

“You might say, why do the vets and farmers want to do this, because if you go and address problems before they arise the vet won’t come out,” says Wall. “But actually, what you’re doing is offering a whole-health outlook. So, they’re having to change from where they were going out and treating a lame cow, whereas now they’re working with farmers to make sure the cows don’t get lame in the first place.”

This approach to agritech, where artificial intelligence is combined with the practical knowledge and skills that farmers and agricultural professionals already possess, is making a difference on farms around Scotland, says Wall. But it doesn’t come without problems around adoption and equal access to equipment.

In theory, if an individual sheep farmer has the funds to invest in wearable health trackers for all his sheep and does so, all should be well. The farmer will now reap the benefits of tracking the status and location of all their sheep, without having to trek across windswept hills in search of a lost lamb.

But in reality, the farmer will now incur the costs of storing and processing the data they collect. These hidden costs occur within almost every piece of tech, putting the farmer under pressure to pay for multiple services that can decipher and store the data that could, potentially, save them money in the future.

“Particularly from a cropping point of view, some of the kit might be prohibitively expensive at the entry point,” says Wall. “For those farmers that might be on a margin and not making a lot of profit before subsidies, this could increase the technological gap within our country.”

If small farms and farmers can’t keep up with the demands of purchasing technology that is evolving on an almost daily basis, they risk losing out to larger operations that can absorb the cost of adapting with the times. By hiring trained staff and investing in sophisticated systems to analyse and utilise the data that they collect, these farms could increase their share of profits in Scotland while also reducing their costs, squeezing small farms out of business.

In anticipation of these challenges, the Scottish Government opened the Future Farming Investment Scheme in July. The scheme is designed to improve business efficiency and resilience for farmers while also increasing the environmental performance of their farm. The current scheme has a funding grant of £14m for 2025/26, which NFU Scotland president Andrew Connon says needs to be increased.

“The FFIS has been a refreshing step forward – simple, focused, and impactful,” Connon said in a letter to rural affairs secretary Mairi Gougeon. “But unless the funding matches the demand, we risk losing momentum at a time when the industry is crying out for action.”

The grant allows for upfront payments of up to £20,000 to farmers, but the scheme received an overwhelming number of applications, according to the NFUS, meaning applications far outstripped the available grant funding.

In response, the NFUS has asked the government to immediately increase funding for this year’s iteration of the scheme by £5m using funds diverted from a scheme earmarked for food processing and marketing support. The union is also asking that part of the £26m budget for the scheme’s 2026/27 iteration be brought forward to cover the cost of reallocating those funds.

An abandoned lime kiln photographed by a drone | Supplied

An abandoned lime kiln photographed by a drone | Supplied

“The demand shows that Scottish farmers and crofters of all sizes, types and locations are ready to invest in their futures,” said Connon. “Not just for profitability, but to deliver on the Scottish Government’s ambitions for climate, environment and resilience.”

Despite the numerous challenges facing the farming sector, those on the cutting-edge of agritech are optimistic about Scotland’s ability to adapt as technology revolutionises the world around us.

“I think Scotland has got a really unique opportunity in this,” says Wall. “We’ve got real agritech skills, we’re one of the leading centres of AI globally and we’ve got a real microcosm of farming types within Scotland.”

In Scotland, over five million hectares of land are dedicated to farming – 66 per cent of the country’s total land area. These farms range in output from livestock farming to cereals, grasses and potatoes across the varying landscapes that make up Scotland. Because of this variety in landscape and farming types Scotland provides, Wall says the potential for innovation is huge.

“Scotland really could become the testbed of pushing AI and other tools,” Wall says. “We have the micro-engineering capability to really develop the next generation of affordable gizmos and robots, those things that are affordable and could be deployed to reduce the barrier to entry into really taking advantage of this technology. I think Scotland as a whole could really be a centre point for agritech that serves all in the era of AI.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe