Suffering in silence: Over two-thirds of MSPs say they have experienced mental health issues

When Labour MP Nadia Whittome announced last month that she was taking time off due to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the reaction spoke volumes about both the progress made in addressing the stigma around mental ill-health and the way still to go.

Whittome, who at just 24 is the youngest member of the Commons, said she was acting on medical advice, and hoped that by being upfront she would allow others to talk about their own mental health struggles.

After posting her statement on Twitter, it didn’t take long to see why the stigma remains so stubbornly fixed.

“Resign and let’s have a by-election. Constituents need a fully functioning MP,” came one of the responses.

Another tweeted: “She should resign and give someone else a chance!”

While the overwhelming majority of responses were kind and supportive, the negative comments show how far we still have to go before taking time off for mental health reasons becomes the norm.

Would those calling for a by-election have done so had Whittome announced a cancer diagnosis, a heart attack or something more prosaic like a sports injury? It seems unlikely.

Despite all the progress that’s been made and all the evidence to the contrary, there remains a widely held suspicion that someone with mental health issues just isn’t cut out for a career in politics.

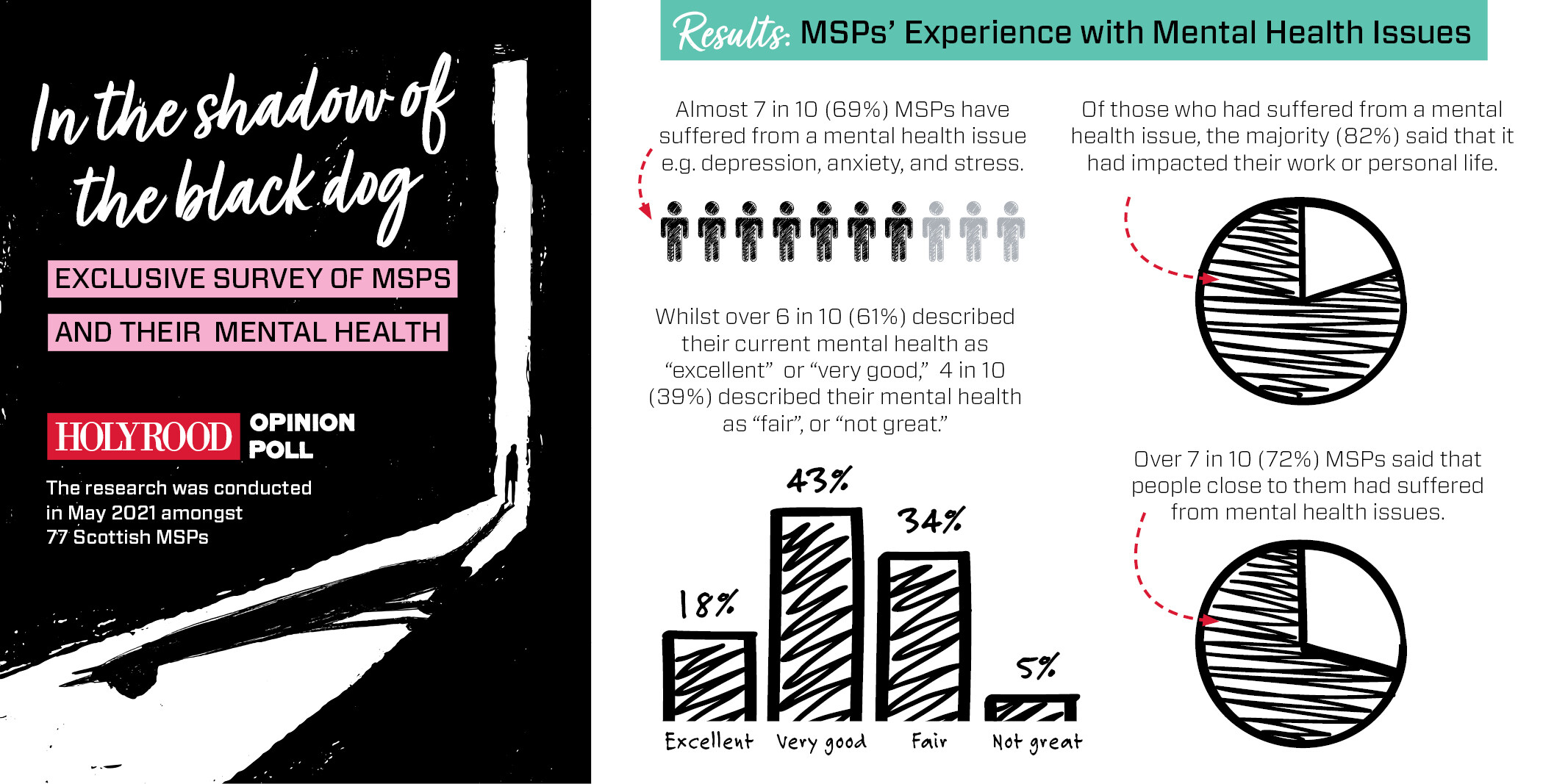

Following the election in May, Holyrood sent a survey about mental health to all 129 MSPs.

Of the 71 MSPs who responded to a question about whether they had ever suffered from a mental health issue such as depression, anxiety or stress, 69 per cent said they had.

“No one cares about the mental health of politicians, so any issues are best kept private to avoid criticism on social media,” was one of the responses from an anonymous MSP.

Another said: “In the political arena, it deserves even more focus – it is a cut-throat environment where few can be trusted...”

We live in a strange political climate where many seem to expect our politicians to represent us without showing any of the frailties that make us human.

Yet the belief that someone somehow isn’t cut out for politics if they have a mental health condition is not only ignorant but ahistorical.

Winston Churchill famously referred to the “black dog” of depression, while Abraham Lincoln is said to have battled “melancholy” and suicidal thoughts.

Indeed, according to a 2009 study, nearly half of US presidents between 1776 and 1974 met the criteria for suggesting some sort of mental ill-health, whether depression, anxiety or bipolar disorder.

Our survey found that of those MSPs who had suffered from a mental health issue, the majority (82 per cent) said that it had impacted their work or personal life.

MSPs reported that mental ill health had led to a loss in confidence as well as a lack of focus, insomnia and anxiety.

Family relations were strained due to short tempers, mood swings, disinterest, and depression.

And nearly 90 per cent of those surveyed felt there was a continuing stigma associated with mental health issues.

“Politicians are human too; we have our frailties like anyone else. Robust support mechanisms are important and having the confidence that the services offered through parliamentary channels or otherwise are highly professional is essential,” one of the MSPs responding to the survey said.

Among those responding, nearly half (43 per cent) described the current state of their mental health as “very good” and 18 per cent considered it to be “excellent”. However, five per cent of respondents answered “not great”.

Of those who had suffered from mental health issues in the past, less than a third had sought any help, such as visiting their GP, taking prescribed medication or attending therapy/counselling.

In terms of taking care of their mental health, maintaining a sense of purpose (70 per cent), exercising (68 per cent), and sharing problems with friends and loved ones (64 per cent) came in as the top three ways of coping.

However, 14 per cent of respondents said they “managed” their mental health with alcohol.

One MSP responding to our survey said: “There are very few options readily available to anyone suffering the early stages of poor mental health.

“If one hasn’t already developed a coping mechanism, there is nowhere to go. Many of the coping mechanisms that were learned in childhood, that were in place previously have been stripped out of communities - especially in the school environment.

“If long-term societal strategy is not considered, the mental health crisis will only increase. In my view, parliament is not set up for this kind of intervention.”

In reality, the life of a politician is often inimical to good mental health.

All the things we’re advised to do in order to look after ourselves – avoid stress, get enough sleep, eat well – are difficult amid the cut and thrust of daily politics.

Those things were true even before the pandemic made life more stressful for us all.

But another consequence of the pandemic is that it has become more difficult to access help.

Figures from Public Health Scotland show that in the three months to March 2021, 18,030 people started psychological therapies within the NHS.

While that figure represents a 5.9 per cent increase on the previous quarter it remains 1.3 per cent below the same period the previous year, just before the start of the pandemic.

Just over 80 per cent of people started their treatment within 18 weeks, up slightly on the previous quarter but below the Scottish Government’s 90 per cent target.

The new health secretary, Humza Yousaf, has said the Scottish Government will bring forward a blueprint within its first 100 days, setting out how the NHS and mental health provision will recover from the pandemic.

In terms of addressing access to mental health provision, our survey appears to show he will have support from colleagues across the Chamber.

Almost all of the MSPs surveyed (95 per cent) said they wanted to see greater parity between care for mental and physical health within the NHS.

Over two-thirds of MSPs (67 per cent) thought that every employer should recruit mental health first aiders.

Scotland is by no means unique when it comes to grappling with the issue of mental health.

Nor are our parliamentarians unusual in their experience of well-being.

In 2019, a survey of MPs found around three-quarters of those who responded to a poll were suffering from poor mental health.

The study, which was led by psychiatrist and Tory MP Dr Dan Poulter, found members of the House of Commons were much more likely than either the general population or those in other stressful occupations to be troubled by distress, depression and other similar conditions.

Poulter described the results as painting a “worrying picture”, with 42 per cent of those who responded to the survey having “less than optimal mental ill-health,” while 34 per cent had “probable mental ill-health”.

Only around a quarter of those who answered the questionnaire had “no evidence of probable mental ill health”.

The study concluded that most MPs did not feel that they had adequate mental health support, and they lacked knowledge of how to access the mental health services that are available to them.

Most MPs were not able to discuss their mental health problems with their Whips or other MPs. The findings indicated that better support was required both to prevent mental health problems among MPs and to ensure rapid and effective care when needed.

Our survey highlighted a similar picture of MSPs struggling to cope with the demands of the job and family life.

“I was often very distant from my family and would regularly lose my temper with the kids for even the smallest thing,” one respondent said.

Others spoke of reduced work rate, feelings of guilt about work/life balance, as well as low mood and anxiety.

“I felt suicidal and often barely able to function. I developed obsessive thoughts,” one MSP told us anonymously.

“Black dog days make no room for family,” another said.

Others reported loss of sleep, “lost days” to depression, self-medication with alcohol and cancelling events due to low mood.

“I became bad-tempered and lacking in patience,” one MSP responded. “I lost interest in my job and avoided doing all but the necessary.”

The charity See Me, which receives funding from the Scottish Government and Comic Relief, seeks to end the stigma around mental ill-health.

Spokesman Nick Jedrzejewski says there remains a “culture of silence” around mental health in many workplaces.

“There has been a real shift in general in discussing mental health, but it’s still difficult when you’re the person that’s struggling and you’re worried about the impact that speaking out is going to have on your life and your career.

“With MSPs, they’re all in high-pressure jobs and roles that are accountable to the public. If no other MSP is speaking out or appears to be struggling, they may wonder ‘why am I struggling?’

“By one or two people not speaking out, it then has that knock-on effect and that creates the culture of silence around mental health.”

Jedrzejewski raises the case of Naomi Osaka, the US tennis player who withdrew from the French Open after refusing to speak to the media at the tournament.

Osaka, 23, says she has suffered “long bouts of depression” since winning her first Grand Slam title three years ago.

“At See Me we ask that in workplaces if someone is struggling with something, a reasonable adjustment can be made to help people stay in work. The reaction that (Osaka) received was that she might get disqualified and then when she dropped out, it wasn’t an entirely supportive reaction across the media. Other people in the public eye would have similar worries.”

A common refrain among those surveyed was the need to give children the emotional armoury to tackle mental ill-health from a young age.

“We need to start providing young people while at school with the skills and tools to as much as possible, look after their well-being,” one MSP said.

“I don’t know if it’s possible for us to live life without experiencing challenges to our mental health, but having the skills or a network in place when we have to face challenging times will go a long way to helping more people feel they have support.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe