An intoxicating mix: getting to grips with Scotland's addiction to alcohol

When July brought the devastating, though not entirely unexpected, news that in 2020 Scotland racked up a record number of drugs deaths there was no shortage of government ministers with platitudes to offer.

Drugs policy minister Angela Constance called the 1,339 fatalities “our national shame” while First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said the numbers were “shameful” and “unacceptable”, and that every life lost was a “human tragedy”. Vigils were attended and an extra £250m of funding for services was swiftly found.

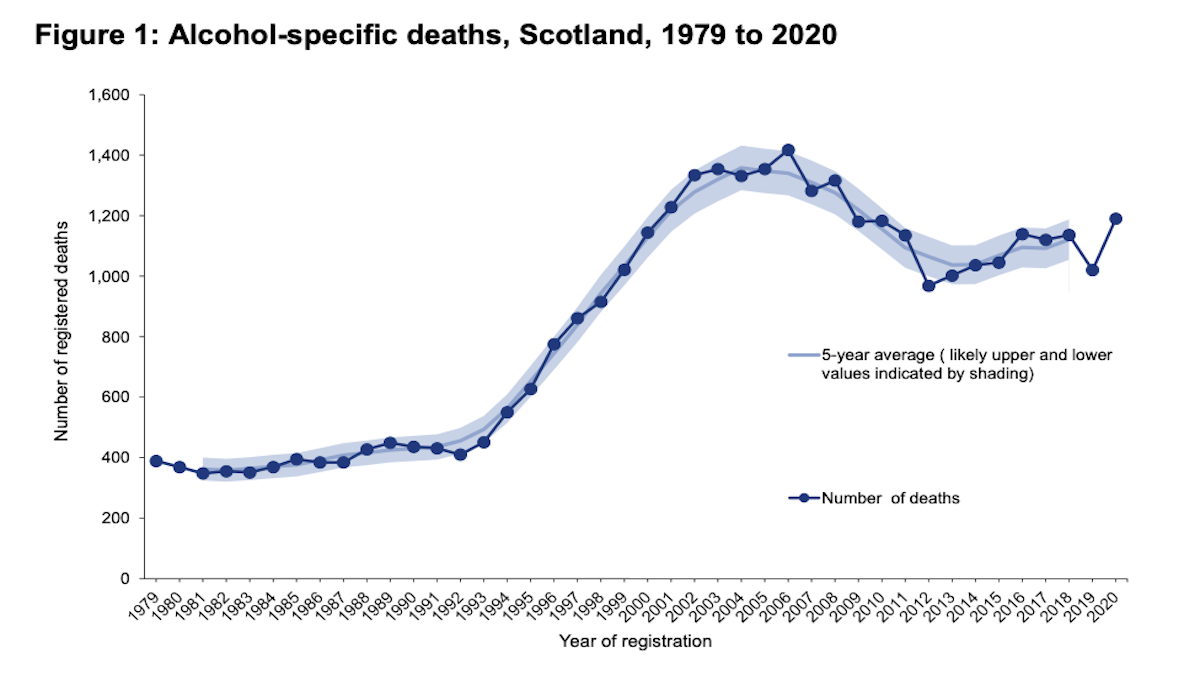

Yet when August brought the news that there had been 1,190 alcohol-related deaths in the same period - a figure that was up 17 per cent on the previous year against a five per cent rise in drug-related deaths - the response was decidedly more muted.

Public health minister Maree Todd painted the spike as an anomaly, something that could be put down to the lockdown effect. If extra funding for services is planned, it is yet to be announced.

For Justina Murray, chief executive of the charity Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs, the lack of an outcry so soon after hands were wrung over the drug-death numbers was disappointing but not particularly surprising given the way that alcohol consumption - even excessive consumption - has been normalised within Scottish culture.

“The political fallout of the alcohol death figures was non-existent – ‘it’s all to do with the pandemic, let’s move on’,” she says.

“In general, people just don’t like to look too closely at the alcohol issue because it’s so much part of our society. Even looking at the pandemic, the coverage of alcohol was quite light-hearted – it was the only way to cope with homeschooling, there were celebrations when beer gardens reopened – but the deaths show there’s a dark side to this too. For Scotland that’s the real issue.”

Source: National Records of Scotland

Scotland has long had a complex relationship with alcohol, on the one hand playing up to its hard-drinking, fun-loving image while on the other demonising anyone who develops a problem with drink.

Alison Douglas, chief executive of Alcohol Focus Scotland, says this is partly to do with the way alcohol has historically been seen as “socially acceptable and highly normalised in our society”, which in turn is to do with the way that has been driven by commercial interests.

“Alcohol is heavily promoted and we see it as an integral part of our social lives and interactions - we use it to relax, socialise and console ourselves and there isn’t an occasion where alcohol isn’t seen as a desirable part,” she says.

“We collude in that because it’s almost part of being a fun person, a social person, and anybody who stands apart from that and says they don’t want to drink very often has pressure put on them.”

Marketing is also used by drinks companies to abdicate any responsibility for the problems their products help create. Yet Douglas believes that urging people to ‘drink responsibly’ - a campaign orchestrated entirely by the drinks industry itself - only serves to reinforce the stigma that surrounds alcohol dependency.

“Responsible drinking invites us to judge other people’s drinking,” she says. “It’s those people over there, they let the side down, if it wasn’t for them we wouldn’t have a problem in Scotland.”

But if marketing is part of the problem Scotland faces with alcohol, it must be part of the solution, too.

Back in 2010 members of the World Health Organization agreed a global strategy for reducing the harmful use of alcohol. While that was made up of 10 “target areas for policy options and interventions”, the list has since been reduced to just three: “increasing taxes on alcoholic beverages, enacting and enforcing bans or comprehensive restrictions on exposure to alcohol advertising across multiple types of media, and enacting and enforcing restrictions on the physical availability of retailed alcohol”.

Public health minister Maree Todd said the increase in alcohol-death figures could largely be explained by lockdown

Scotland has been at the forefront of using taxes as a means of reducing consumption, fighting a long legal battle against the drinks industry to eventually introduce a minimum unit price (MUP) of 50p in May 2018. Early indications are that it has been a legislative success, with a study published in The Lancet earlier this year finding that alcohol sales fell by close to eight per cent after the policy was introduced and a series of reports from Public Health Scotland indicating that that has led to a reduction in harms.

For Elinor Jayne, director of Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP), the policy does not go far enough, though. Noting that 50p per unit was the price mooted when the policy was first floated almost a decade ago, Jayne says if the government was serious about reducing alcohol-related harms it would increase that price point with immediate effect.

“A first step would be to increase MUP from 50p to 65p because that’s just been left to trundle along,” she says.

Douglas, too, says she is “strongly in favour” of seeing MUP rise, in part to take account of inflation - 50p in 2012 equates to 61p today - but also to “increase the benefit it’s delivering”. Yet she stresses that without similar action to address both the availability of alcohol and the way it is marketed, the impact of MUP will remain limited.

“We need to control availability because at the moment we are reliant on a pretty permissive licensing system,” she says.

“Local licensing boards can reject applications but they can’t actively reduce the number of licences or the amount of alcohol that’s sold in a local area. We need to have a look at how we control the amount of alcohol available in particular areas. You are four times more likely to die an alcohol-related death and four times more likely to be hospitalised if you live in a poorer area, but there are more licences available in those areas.”

If you have a physical and psychological dependency to alcohol then you’re going to do what it takes to maintain that dependency – you have to

At the same time, the marketing of alcohol remains an ever-present feature of our daily lives. A study carried out at the University of Stirling on behalf of SHAAP, the Institute of Alcohol Studies and Alcohol Action Ireland found that during games featuring Scotland, England, Ireland and Wales at the 2020 Six Nations Rugby Championships - an event sponsored by drinks giant Guinness - adverts for alcohol appeared once every 12 to 15 seconds.

This is problematic, says Nathan Critchlow, a research fellow in the University of Stirling’s Institute for Social Marketing, because there is now four decades’ worth of research that shows a causal link between children being exposed to alcohol marketing and going on to drink more in adulthood (research from Alcohol Focus Scotland also found children can more readily recognise beer brands than biscuits).

Work is starting to be done on whether there is a similar effect on vulnerable groups such as those in recovery from dependency, but Critchlow notes that a consultation promised in 2018 on whether controls on marketing should be introduced has yet to be launched. Former SNP MSP Linda Fabiani asked the government in February when it intended to start that consultation; according to the Scottish Parliament website the current status of that question is “awaiting answer”.

Even if these three policy strands went far enough to, when combined, make a meaningful impact on people’s lives, that impact would only be felt by those who have not yet developed a dependency on alcohol.

Jardine Simpson, chief executive of the Scottish Recovery Consortium, notes that MUP, for example, had proved to be good at preventing people reaching the point of addiction, but for those already addicted, no amount of marketing blackouts or pricing spikes will be enough to reverse that.

“If you have a physical and psychological dependency to alcohol then you’re going to do what it takes to maintain that dependency – you have to,” he says.

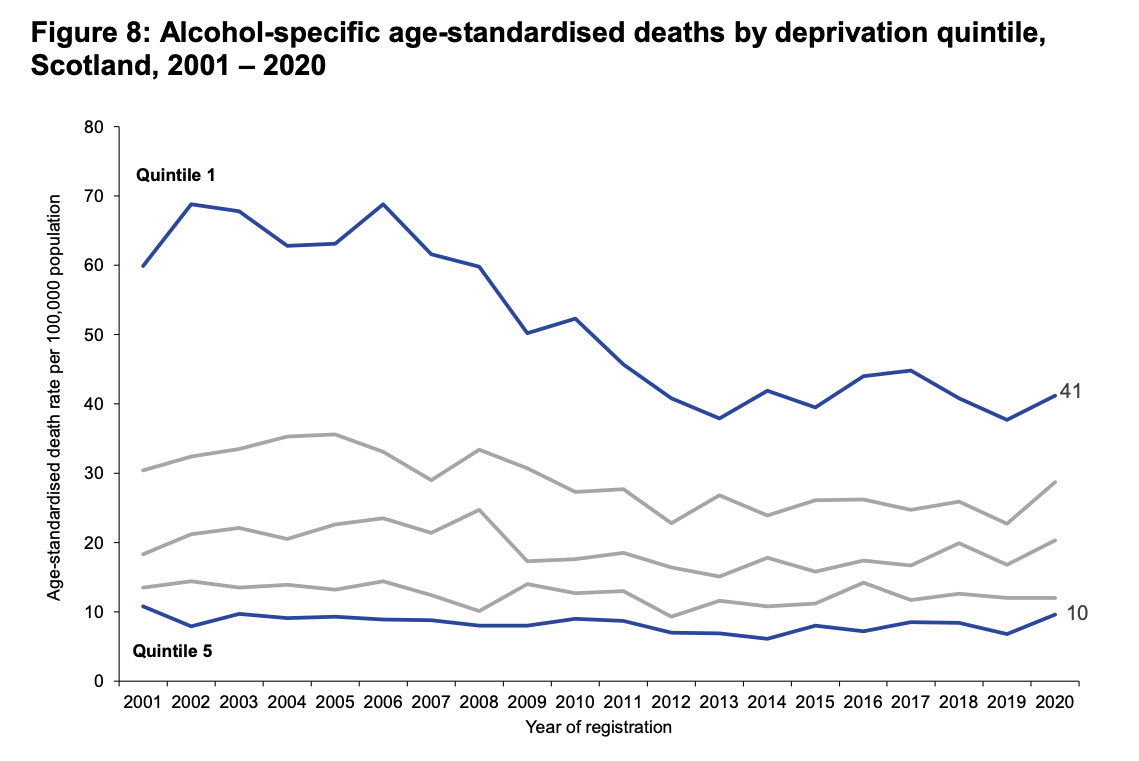

In that respect, taken in isolation MUP - Scotland’s most-advanced dependency-prevention measure - can be seen as a regressive policy. The death figures show that in areas classed the poorest by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation, 41 people in 100,000 died an alcohol-related death in 2020 against 10 per 100,000 in those classed the richest.

Source: National Records of Scotland

That chimes with the findings of reports such as Public Health Scotland’s slcohol related hospital statistics - which found that in 2019 people in the most deprived areas were seven times more likely to be admitted for an alcohol-related condition than those in the least - and the government’s Scottish Health Survey - which found that, while dangerous drinking is more prevalent in wealthier areas, hazardous drinkers in the poorest areas consume the highest number of units per week.

That means that, without well-funded, accessible services designed specifically to reach people already in addiction, Scotland’s current alcohol policy-making runs the risk of benefiting the wealthy at the expense of the poor. Yet statutory treatment services, which Audit Scotland deemed to be patchy in 2009, remained inadequate in the years leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic.

In an update to its drug and alcohol services report published in 2019, Audit Scotland found that funding for treatment services varied widely across local authority areas and that “outcomes for many people misusing drugs and alcohol have not improved over the last 10 years”. Murray says that in the past 18 months they have got a whole lot worse.

“We know alcohol and drug use has gone up [as a result of the pandemic] and treatment services have shut their doors,” she says.

“People are paid to answer the phone but there are services that are just not responding. Why are phones not being answered? Why are answer-phone messages not being returned? Why do most treatment services not have a freephone number?

“We found during the pandemic that the trend away from voice-based calls was very rapid. At the moment only a fifth of our contact is over the phone, four-fifths is via webchat or text message. People can do that really discreetly. They can sit on a website and reach out for support for free and in secret. Statutory treatment services don’t offer those types of options. It used to be the front door and the phone but now the front door is closed and the phone may or may not be answered. It’s pretty ropey.”

Though there is obvious frustration that those services are not readily available to everyone who requires them, Jayne says even in areas where provision is strong people miss out because of the way alcohol dependency continues to be viewed by society.

“Stigma is real,” she says. “A lot of people will judge someone with an alcohol problem and think they have somehow brought it on themselves, which isn’t the case. This needs to be seen as a health problem.

"We are told by the drinks industry to drink responsibly, but that just puts the onus on the individual to own their own consumption. If we still stigmatise people who have a problem with alcohol then of course they are going to have a problem asking for the help they need.”

This, for Simpson, is the crux. Pulling all the strands of prevention and cure together in a transformational policy bundle is one thing, but bringing about the attitudinal change needed for those policies to stick is where the Scottish Government’s real challenge will lie.

“The issue here is that Scotland’s - and most developed countries’ - attitude towards alcohol is that it’s primarily a beneficial social lubricant, but alcohol is a toxic substance to the human body and its perceived beneficial effects are subject to that,” he says. “It’s a cultural issue that we need to address - the narrative and therefore the messaging has to change.

“If you want to change the Scottish attitude towards alcohol you have to change the narrative around what it is and what harms people experience if they develop a dependency to it. We need to educate but also empower people to understand alcohol in a different way.”

Owning the alcohol-death figures in the same way it did the drug-death statistics would have been a good place for the Scottish Government to start that process.

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe