The care conundrum: Why care homes are not the magic bullet that will fix the NHS

Former MSP Neil Findlay is used to advocating for his brother John. Before he stood down from Holyrood at the last election, the then representative for the Lothian region even mentioned his older sibling in a 2014 parliamentary debate, highlighting how John – who has multiple sclerosis (MS) and relies on a wheelchair for getting around – had been let down and humiliated on a holiday flight. John, Findlay said, had been treated “very much like a second, third, or fourth-class citizen” when his airline failed to take account of the assistance he required, leaving him without the help his travel agent had promised.

In the aftermath, concessions were made and the travel agency updated the advice it gives to customers with accessibility needs. But now, almost a decade on, the Findlay family has an even bigger issue on its hands. John’s MS has advanced to the stage that he can no longer safely live at home with his wife and step-son and a move into a care home is on the cards. The problem is there are no care home places to be had and, despite having no immediate health needs, John has been stuck in hospital for months with no end to the situation in sight.

“John had social care coming into his house, but it wasn’t working, and he was continually unwell with things like infections,” Findlay says. “He ended up in hospital last year and was there for a month or so before being discharged back home with carers coming in, but then he had to go back into hospital six months ago and has been there ever since. He’s in hospital right now, having been ready to be discharged for months and months, but there’s no place available.”

Former MSP Neil Findlay (right) and his brother John

Former MSP Neil Findlay (right) and his brother John

It is a situation many families will recognise, and is hardly surprising given the sharp fall in the number of nursing homes operating across Scotland in recent years. Public Health Scotland’s care home census shows that in March 2000 there were over 1,600 residential homes in Scotland, the vast majority (1,059) catering for the elderly. By March last year the total number had dropped by a third to just over 1,000.

Part of the reason is that the way some large care home operators funded their expansion was unsustainable. In the 1990s companies such as Four Seasons and Southern Cross easily attracted the backing of private equity investors keen to gain a foothold in a lucrative industry whose fundamentals appeared sound. Property prices would, it was assumed, continue on their upward trajectory while demand for elderly care would continue to soar.

The problem is those private equity investments were funded largely by debt, and debt comes with a sell-by date. When it came time to renegotiate those loans, repayment levels had ballooned and, as some providers had even sold off their properties to other debt-funded investors in a complicated sale-and-lease-back arrangement, the sector found itself in trouble. Southern Cross infamously collapsed in 2012 and Four Seasons went into administration in 2019. Some homes closed, others were sold off and, with soaring interest rates making the debt burden ever-more onerous, operators across the sector have continued to rationalise their portfolios.

Yet as Donald Macaskill, chief executive of industry body Scottish Care, points out, that only tells a tiny part of the story, with the problems in the care home sector running much deeper than a few large organisations’ structural woes.

“Fundamentally, as in all things, this is around resources because the gap between what the state pays for care home provision – the National Care Home Contract Rate – and the true cost of care, as independently analysed, has grown and grown and grown, substantially in the last five years, but has been growing for 10 years,” he says.

The National Care Home Contract was established by Cosla in 2006 after a report from the now defunct Office of Fair Trading found that differing contractual terms meant some care home residents were potentially being treated unfairly. Though it aims to make the provision of publicly funded places more equal, Macaskill says it has had the opposite effect because the Scottish rate of £832.10 a week for nursing care is significantly lower than the £1,300 to £1,500 a week it actually costs to provide that care.

Policies designed to keep people in their own homes for as long as possible – the so-called ‘free social care’ model – mean the vast majority of those entering care homes require nursing rather than residential care and, with only some residents able to pay for that themselves, many operators have been unable to make ends meet and have taken the decision to close. That has contributed to the reduction in the overall care home estate, with rural and remoter communities disproportionately affected.

“People get into a debate here about the private sector creaming off profits, but that’s to wholly misunderstand the nature of the care home sector in Scotland, which unlike England is dominated by small family-run enterprises, often single homes which are much less economical to run, but are in locations where people would want the care homes to be,” Macaskill says.

There are significantly more registered spaces than there are people in care homes, so there are technically a lot of spaces, but care homes are at capacity because of staffing more than anything else

At the same time, even when there are care homes in an area, significant and ongoing workforce issues mean many are operating well below capacity. The reduction in the number of homes is not directly reflected in the number of beds, which fell by five per cent between 2012 and 2022 against a 20 per cent drop in the number of homes, but if operators cannot find enough staff to provide the care, those beds have to be taken out of the availability equation.

“There are significantly more registered spaces than there are people in care homes, so there are technically a lot of spaces, but care homes are at capacity because of staffing more than anything else,” explains Mark O’Donnell, chief executive of the charity Age Scotland. “I’ve been in charities that have had to make incredibly difficult decisions to close facilities because of things like economies of scale, viability, the desire to pay above the living wage – for most charities that just becomes unsustainable in terms of their funding. Overall, there are actually enough registered spaces, it’s that [providers] can’t take people on from a safe staffing point of view.”

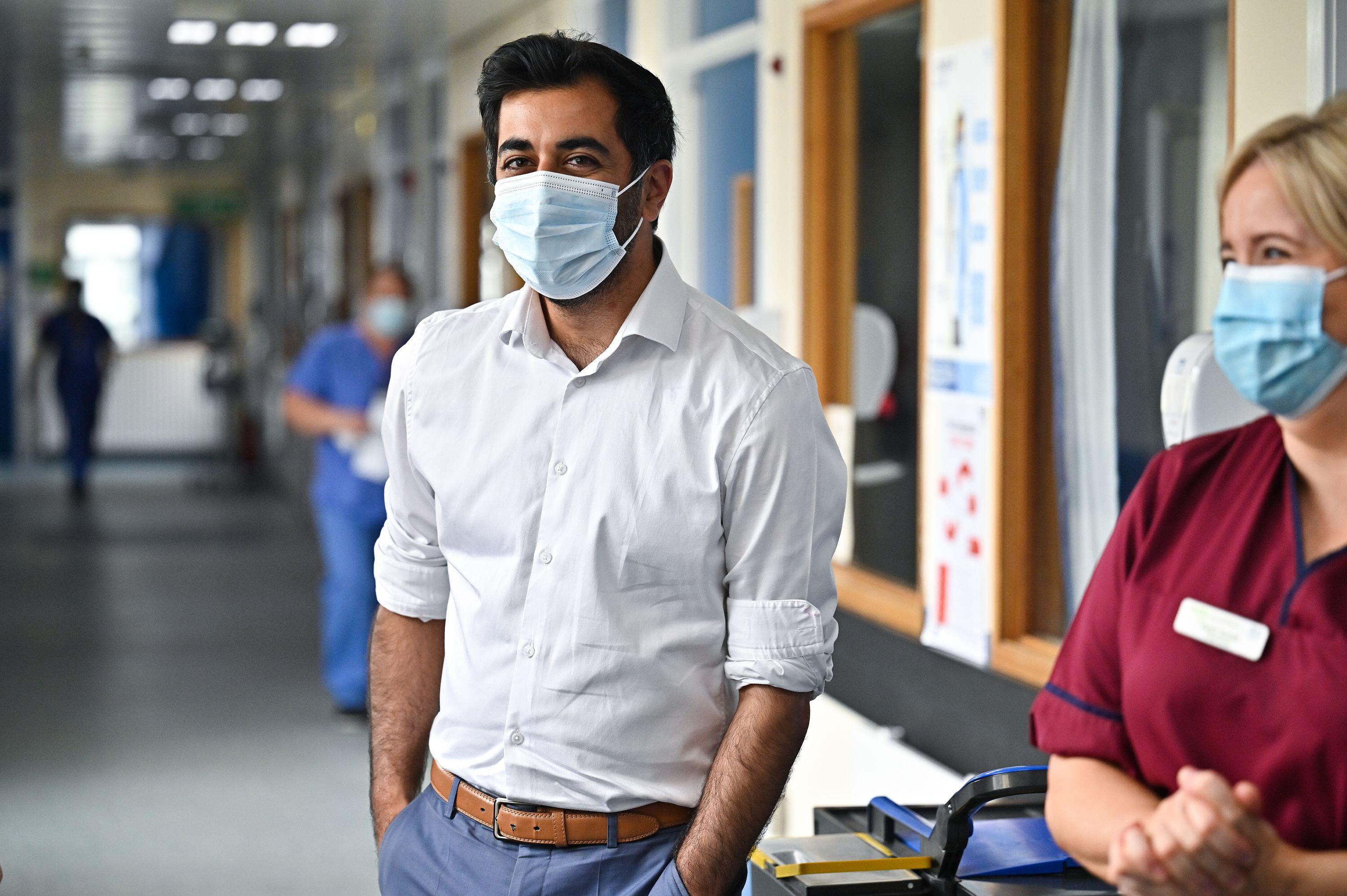

And it is against this backdrop that the Scottish Government has proposed to ease pressures on the NHS by discharging people who are stuck in hospital – blocking beds they are well enough to leave because they cannot find a care home place – into care homes. As announced by health secretary Humza Yousaf last month, £8m has been made available to fund 300 additional interim care beds on a temporary basis as an “extremis, time-limited measure to help us with the current capacity issues that we face”.

Health secretary Humza Yousaf has made extra funding available to discharge hospital patients into care homes

Health secretary Humza Yousaf has made extra funding available to discharge hospital patients into care homes

Though the use of interim care beds is nothing new – around 600 beds have for several years been used to transition people either back into their own homes or on to a permanent care home place – for Alzheimer Scotland director of policy and practice Jim Pearson, the policy risks removing agency from what is by and large a vulnerable group of people whose care needs are already not being met.

“There are a number of issues for people with dementia around how you overcome issues of capacity and consent,” he says. “One of the reasons why a lot of people are in hospitals now and have not been discharged is because there’s no authority for consent. If they can’t consent themselves and there’s nobody with a power of attorney, or there’s no existing guardianship, you have to wait for a guardianship process to get the authority to make that decision. There are issues around the fact that in our hospitals just now there are significant numbers of people with flu or coronavirus and we could make the same mistake as a couple of years ago [during the pandemic]. I know we’ve got vaccines now and it’s a different environment, but even so potentially you could be looking at introducing infection.

“This is supposed to be an interim measure and by my calculations that £8m would last something like six months for 300 places because it is based on the National Care Home Contract Rate plus 25 per cent. What happens at the end of that period and how do we make sure those people don’t just simply then become permanent care home residents without any review, proper assessment or consideration as to whether or not they might be able to get other appropriate alternative arrangements that might support them in the community?”

Back in 2014 the Scottish Government and Cosla asked former NHS executive Douglas Hutchens to lead a taskforce that would come up with “a range of ideas and recommendations to underpin the delivery of high-quality, sustainable and personalised care and support in residential settings over the next 20 years”. In the foreword to the taskforce’s report, Hutchens wrote that “the mark of a caring and mature country is how it treats the most vulnerable citizens within its society, particularly its older people”.

Key among the recommendations was the delivery of a personalised approach that would empower people and care for them rather than simply deliver care to them, with the words for and to highlighted in bold. Crucially, the report said, personalisation “has to be available to all”.

Cathie Russell, a retired South Lanarkshire Council communications manager who set up Care Home Relatives Scotland to help families campaign for better visiting rights after being unable to see her late mother, Rose, during the coronavirus pandemic, says that in reality that rarely happens. The reason, she says, comes down purely to cost.

“If people don’t own their own home and don’t have cash to pay, they’re funded through the National Care Home Contract. But care homes are reluctant to take people for that money – you’re talking about £5 an hour for some of the sickest, most poorly people in society,” she says. “The people who tend to be prioritised are the people for whom there’s a really strong need to get them in somewhere because home carers might be saying they’re not suitable to be at home. A lot of people I’ve been speaking to as part of the campaign have been trying to get their relatives into a care home for a long time.”

She continues: “When my mum went into a home I knew her former council house would have to be sold to pay for it but I worked out that the gap between what the care home was charging and what the council would pay was £27,000 a year. I wrote to the home and said my mum’s money would be gone in two and a half years and I couldn’t pay that difference because I don’t have £27,000 a year. They wrote back and said ‘it’s okay, as long as you have two years of funding we’ll accept council funding after that’. As it happened my mum died after a year and eight months so we didn’t reach that situation.”

With its £8m package, the Scottish Government has made an attempt to solve the funding-related block, albeit on a temporary basis. But while Pearson is concerned that the measure could turn people into care home residents by default, ultimately locking those with assets to sell into paying for places they have been given no choice in securing, Macaskill notes that the fact the government is willing to pay significantly more than the National Care Home Contract Rate for the places only serves to underscore the disarray the entire care sector is in.

It’s a fear of the whole system that we don’t have sufficient staff and that we don’t have sustainable home care organisations to better support people

“There’s that fear that the packages might not be in place at the end of the six-week [transition period] for the 300 extra beds,” he says. “It’s a fear of the whole system that we don’t have sufficient staff and that we don’t have sustainable home care organisations to better support people. It’s also a fear of the care home sector, who increasingly are taking the view that the current National Care Home Rate is simply so far away from the true cost that in order to keep existing residents safe, they will turn down somebody on a state-funded rate if they can and take somebody privately, but if they can’t, it’s probably more economical to have that bed empty than it is to have a bed and have a room occupied by somebody who you’re losing money on because that’s affecting the care and support of other people.

“We urgently need to get that sorted out. Negotiations are underway at the moment [on raising the National Care Home Contract Rate, which happens annually] but unless we get that sorted and raised to a rate which is sustainable for care home providers, especially small providers and especially in rural areas, if we don’t make it economically sustainable for them, then people in remote areas and those who cannot afford to pay will have the least opportunity and chance to get a care home place and potentially to get out of hospital.”

Back in Holyrood, opposition parties are making hay out of the situation the Scottish Government has got itself into, stressing that the SNP-led administration should not be pressing ahead with plans to create a National Care Service, which promises to centralise and revolutionise the provision of social care, when it has been unable to get delayed discharge and residential care under control.

Underscoring the point about capacity in the care sector, Labour’s Jackie Baillie points out that just 473 of the now 900 interim care beds were in use at the end of January and that “the SNP will never remedy delayed discharge unless they get serious about tackling low pay in social care”. Scottish Liberal Democrat leader Alex Cole-Hamilton says numbers that show close to 2,000 people remain in Scottish hospitals despite being fit for discharge prove there is a “systemic crisis in social care”. “The number of people in hospital is stubbornly high and the SNP/Green administration is hellbent on pursuing a billion-pound bureaucratic solution which will only make things worse,” he claims.

Meanwhile, for people like John Findlay the wait to access suitable care – care that is personalised and empowers them to have agency over their own lives – goes on. Though he says the care he has received at St John’s Hospital in Livingston these last six months has been exemplary, Findlay says the frustration he feels at being stuck 11 miles from his family and community in Fauldhouse is very real, not least because the cost of keeping him in hospital far exceeds what it would have done to discharge him with an appropriate package of care.

“I have nothing but praise for the staff who have looked after me in hospital and nothing but condemnation for the government ministers who have got our precious NHS into the state it is,” he says. “As for the social care system, it is a disaster, it is completely unfit for purpose. In my six months in hospital I have repeatedly come across people who, like me, are stuck in hospital beds at a cost of thousands of pounds a week to the NHS when we should be being cared for in our local communities in a more appropriate setting at a quarter of the cost. The system is long past crisis point – it is a frustrating, expensive and at times hopeless disaster for too many of us who through no fault of our own need long-term care.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe