On a personal mission: An interview with Elena Whitham

In some respects, Elena Whitham had an easier job than her predecessor when Scotland’s annual drug-death figures were announced in the summer. The stats were clearly nothing to celebrate – 1,051 people had died from drug misuse in 2022, with the figure sitting nearly four times higher than it did in 2000 and close to three times the average rate seen across the UK in 2021. But, two years after then first minister Nicola Sturgeon was forced to set up a national mission on drugs, the number of deaths had dropped by 21 per cent and Whitham could point to the strategy’s nascent success. Then drugs policy minister Angela Constance had been heavily criticised when fatalities fell by just one per cent in 2021, but with the larger drop Whitham was given a pass.

There was also something about Whitham’s tone that seemed different, though. To call it sincerity would be to do Constance a disservice. The latter had been handed the newly created role of Minister for Drugs and Alcohol Policy in December 2020 after public health minister Joe FitzPatrick was forced to stand down on the back of the previous year’s abysmal numbers. A former social worker whose pre-politics career included a stint in the prison service, Constance talked the talk on turning the tide, her statements peppered with references to heartbreaking statistics, unacceptable situations, and Scotland’s shame, but with fatality rates remaining stubbornly high on her watch the words seemed to ring a little hollow. In fairness, government strategies are never going to bear immediate fruit and Constance, who was promoted to justice secretary when Humza Yousaf succeeded Sturgeon at the head of government earlier this year, probably just didn’t have enough time to walk the walk. But still, rightly or wrongly, Whitham’s commitment to fulfilling the national mission seems more believable, perhaps in part because she has made it clear that for her it is personal.

When she visited Glasgow rehabilitation project Back on the Road on the day the 2022 figures were announced, Whitham told reporters about a family member who had been addicted to substances and had a “hard-fought” battle to find a route to recovery. With every death listed in National Records of Scotland’s annual stats release corresponding to a person, and with every one of those people leaving behind a network of devastated family and friends, Whitham said she understood “the fear that people have every single day that something is going to happen to their loved one” because she and her wider family have felt it too.

When we sit down in housing minister Paul McLennan’s Holyrood office, borrowed for the hour because Whitham shares with community safety minister Siobhian Brown, she talks more about what her family has been through. Her relative was addicted to heroin, she says, something she had seen a lot of when living in a Kilmarnock estate known as The Scheme in the nineties. The relative was also “there for the beginnings of street Valium”, the potent benzodiazepine-based sedative that is highly addictive due to even a tiny decrease in dosage causing severe side-effects including terrifying seizures. An addiction to the two is notoriously difficult for users to escape from and for a while Whitham’s family feared their loved one never would.

Yet while her relative finally felt ready to attempt recovery around five years ago, Whitham says they kept coming up against a brick wall, the wait for the prescription needed to ease them off illegal drugs stretching to months while the window of opportunity for reaching someone looking for help with addiction is in the here and now. She had witnessed people facing the same challenges while working for Women’s Aid 10 years before, but Whitham says she was shocked to discover things hadn’t improved since. Having been appointed deputy leader of East Ayrshire Council not long before, she started pushing for change.

“I was working hard to say that this was not good enough – it was still the same place we were at when I was supporting people 10 years previously and they were waiting months to get a prescription,” she says. “That was the issue for my family member. […] It’s night and day in East Ayrshire now compared to five years ago. You can get a prescription on the same day; there’s a recovery hub on the main street in Kilmarnock where all agencies come together. Tangible differences are happening and I can see that from direct, lived family experience. My family member is in recovery and has been in recovery for five years, which is fantastic. They even maintained that through losing their best friend to a drug-related death. It’s so difficult to lose your closest friend and as a family we were terrified what would happen to them at that time.”

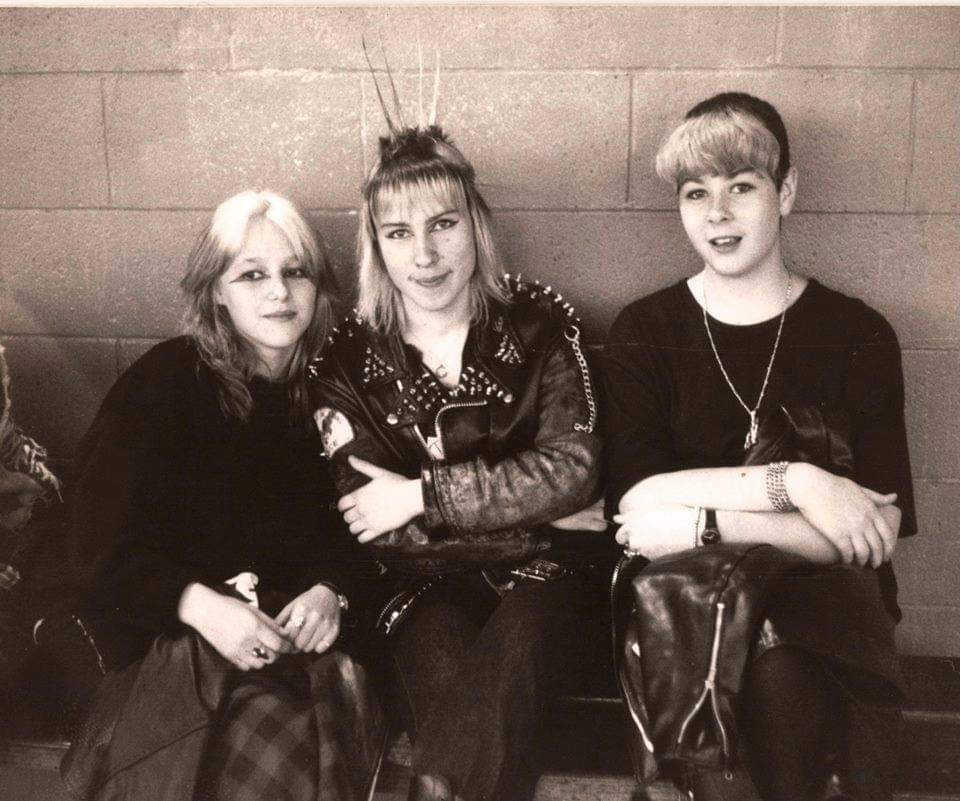

Though that experience was relatively recent, Whitham says she first witnessed someone using heroin when she was a teenager living in Montreal in the late eighties and hanging out with friends in the punk scene there. Her family had moved to Canada when she was six, her young parents uprooting her and her younger brother after the Kilmarnock factory her father worked in shut down. Emigration was supposed to be the making of the family, but they fell into extreme poverty when the Canadian company her dad had been sponsored by also closed its doors. The experience had a traumatic impact on the young Whitham and, while recreational drug use was common in the countercultural circles she moved in, she says that even at a young age she recognised that for some of her friends using heroin was a means of dealing with their own trauma.

“When I was growing up there was always substance abuse; growing up in Canada as a young punk and having lots of friends who were street-homeless punks,” she says. “The first time I encountered someone using heroin I was 15 and they were 16. A lot of the time when it’s not been recreational, it’s been to block out something for them.”

A teenage Whitham (right) with friends in Canada

A teenage Whitham (right) with friends in Canada

Canada shaped Whitham but it was a world of extremes for her too. She vividly remembers catching a double-decker plane from Prestwick Airport and stepping off into a place so shockingly hot she felt like she could “touch the atmosphere”. The family quickly settled into a “quintessentially North American” life, though, encountering peanut butter and McDonald’s for the first time and enjoying life in their new home in Mississaugha, a city neighbouring Toronto on the shores of Lake Ontario. “It was like Stranger Things but without the other-worldly beings,” Whitham smiles. But the loss of her father’s job meant that that idyll was quickly shattered.

“For me this is really critical to my outlook and my upbringing – the company my dad had worked for ended up closing within a year and a half of us being there and my mum ended up having to work shifts in Tim Hortons doughnut shop,” she says. “We were in extreme financial difficulty as a family and we had no family there to help us. For a period we were fed by foodbanks. I was very, very aware of that and aware of the pressure that put on my parents, who were still very young – my mum was 17 when I was born and my dad was just turning 19. When I went home from school I never knew what would be for dinner; I never knew what would be in my packed lunch. That was a period of trauma for me.”

After an 18-month period in which the family took in a lodger – an Italian named Big Al, who listened to AC/DC and taught Whitham’s mum how to make spaghetti bolognese – they relocated to Montreal in Francophone Québec after her dad secured a job at aerospace company Pratt and Whitney. The family still struggled financially – Whitham says none of them can bear the thought of meals like toad in the hole after her mum was forced to make “really cheap food with cheap sausages and beans” – but Whitham says she experienced anxiety of a different kind in Quebec due to the strictly policed language laws in place there.

“I was nine when we moved to Montreal, and there was a language barrier but we had to go to French school because local laws say immigrant children have to be educated in French,” she says. “When we first moved out there I had to adopt a Canadian accent really quickly but then to get to Quebec and try to learn French was really traumatic for me for a while. Within six months of being in that French school I wasn’t coping because I was so stressed. Then someone told my mum that the local Catholic school, which was bilingual, was taking immigrant children and quietly putting them on the school roll. Any time the language police came we were hidden in the art room – the smell of powder paint really evokes that for me. They would phone my mum and she would come and sneak us out then take us back later when the language police had gone. There are 10 of us [that that happened to] who are still in touch as adults. You can’t live in Quebec and not become bilingual, though. Within a year I was able to do it.”

Aside from the poverty and the stress of being thrown into an education system she didn’t initially understand, Whitham says one of the biggest upsets she experienced on moving to Canada was being separated from her family. Her father was the eldest of nine siblings and her mum was one of four and at the time they emigrated all Whitham’s grandparents and a set of great-grandparents were still alive. Being wrenched away from a network that now includes “40-odd” cousins was difficult, to the point that she wouldn’t initially speak to her parents after they made the move. Coming back was just as hard, as she discovered when the family made the return journey when she was a 22-year-old university graduate, her brother Graham had just completed high school and their younger brother Kevin, who was born in Canada, had just finished elementary school.

“It was weird because in Canada we always talked about when we would go home and Scotland always felt like home, then when we came back Canada felt like home,” she says. “I was so glad to see my family again, but I’d left all my friends and frames of reference in Canada. My husband talks about things that were on TV when he was growing up, but I wasn’t here so I don’t know what he’s talking about. I did journalism and communications at university and was a music journalist for a while – I had an offer to work for a record company as an A&R rep, scouting for talent, but I turned it down to come back to Scotland. When I came back here I wanted to write features for broadsheet papers, but I ended up working for local papers, freelancing for the Kilmarnock Standard and Ayrshire Leader. I was looking to find work anywhere but everyone kept saying ‘you’ve not been in Scotland long enough, you’re Canadian’. Eventually I was heading towards the tabloid end so I ended up doing other things.”

As a child with her younger brother

As a child with her younger brother

The first of those other things was working for a youth homelessness charity before she moved on to Women’s Aid, spending 10 years there as a refuge worker. The latter experience was, Whitham says, “wonderful, privileged and harrowing all at the same time”, with the privileged part coming from “being part of women’s journey from an abusive situation to a tenancy of their own”, and the harrowing part coming from seeing “more and more people coming in using substances”. “Many didn’t have care of their children any more, compounded by abuse and substances,” she says. “We were the first group to get funding for an addictions worker. I felt that was really important because I could see more and more women coming through the doors experiencing those issues.”

When she left Women’s Aid Whitham helped her then husband set up a tattoo studio in Kilwinning, sterilising the equipment, taking care of the business side of things and acting as a guinea pig – she has nine tattoos, eight of which were done by him. She also ran four Slimming World groups across Ayrshire. “At that point I’d lost nearly seven stone,” she says. “I loved that, loved being a facilitator. I feel mutual aid and support is really powerful.”

Politics was something she’d always been interested in, though, and when the opportunity to stand for elected office presented itself she seized it. Though her dad’s family had started off Labour while her mum’s leant more towards the SNP, by the time of the referendum in 2014 – the same year her mum, Irene, passed away at the age of 58 – the entire family was Yes. Whitham, who had briefly joined the SNP on returning to Scotland from Canada, campaigned as part of the Women for Independence movement then the morning after the vote “had a burning passion to rejoin”. The following year she won a by-election to replace Irvine Valley councillor Alan Brown, who won the Kilmarnock and Loudon seat at the General Election. She was handed cabinet responsibility for housing soon after, got re-elected and became deputy leader in 2017, and went on to become Cosla’s community wellbeing co-lead alongside Midlothian councillor Kelly Parry.

It is easy to see how Whitham rose through the ranks so quickly. She is clearly intelligent, capable and compassionate, and, while some politicians can give the impression they are struggling to remember the parameters of their brief, she seems fully immersed in hers. Still, she admits to being surprised when she was asked to take over as community safety minister last year after Ash Regan resigned from the post rather than vote for the government’s controversial gender reforms. Though she knew she had the skills and experience needed to handle the role, Whitham had only been an MSP for 18 months, having won the Carrick, Cumnock and Doon Valley seat vacated by former health secretary Jeane Freeman in 2021. Being asked to step up by Sturgeon was, she says, awe-inspiring.

“I was sitting in the chamber and [then culture minister, now wellbeing economy secretary] Neil Gray sat down in front of me and smiled and I thought ‘what are you smiling for?’,” she says. “Then Keith Brown [who was justice secretary at the time] came and tapped me on the shoulder and said ‘there’s someone to see you at the back of the room’. I thought ‘oh God, is this happening?’. It was [government chief of staff] Colin McAllister and he said, ‘I think you know what I’m going to ask you’. Going in to see the first minister, it’s hard to describe how that feels. I know the Cosla experience shadowed community safety and working for Women’s Aid for over a decade I knew I had the skills to hit the ground running, but it was still awe-inspiring.”

When Yousaf replaced Sturgeon earlier this year Whitham replaced Constance in the drug policy role and community safety went to her friend Brown, the fellow Ayrshire lass she shares not just a Holyrood office but a similar life story with (like Whitham, Brown was born in Scotland, spent many years living abroad – Australia in her case – before returning as an adult and getting involved in politics in 2014). Whitham briefly made the headlines during the summer when WhatsApp messages in which she called Deputy First Minister Shona Robison a “cold fish”, culture secretary Angus Robertson “the ego”, and Tory MSP Brian Whittle a “prick” were leaked, but for now she is best known as the minister in charge of the government’s long-fought-for plan to make drug-consumption rooms a success. It is not a responsibility she is taking lightly.

Though drugs policy remains retained to Westminster via the draconian Misuse of Drugs Act – a seventies-era law that takes a hard line on criminalising possession – a Glasgow pilot is to go ahead after Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC last month said she would not seek to prosecute anyone for bringing drugs into such a facility. The UK Government has promised not to interfere, but Whitham stresses that it remains a far from ideal situation. First there is the concern that, as long as the act remains in place, a change in either Lord Advocate or Westminster government could see the arrangement binned. Indeed, in Canada, where safe-consumption rooms have for 20 years operated under exemption-from-prosecution deals agreed at the municipal, provincial and federal level, Conservative governments have tried to shut facilities down. Then there is the frustration that a single pilot will neither give the opportunity to test different models or be able to save lives on the scale that is required. Still, with an increase in drug-related deaths over the first six months of this year showing how fragile last year’s improvement was, Whitham is remaining optimistic about what it will be able to achieve.

“What we have at the moment will save lives and we know that in Glasgow there’s a real need for it because around 400 people are injecting in unsafe and unsanitary conditions,” she says. “We know the service will be a gateway for people to get into other support, meeting them there with compassion and making sure they are as safe as they possibly can be and having that relationship with people where we can let them know they are cared for. That opens up being able to address other issues like housing, access to food, access to clothing. I know what that’s like from Women’s Aid – once you have that supportive relationship you can open avenues for individuals who have been the furthest away from services because those services haven’t been geared up for them.

“We know people will use substances. We need to have this so they can have the headspace to assess what their next steps are. When you’re in the middle of that you can’t see any positivity. I think back to all the people over the years that I have supported and how this would have made a difference to them. Thinking about the women I met, I know it would have helped them to recover and keep care of their children. It’s about working across government and the third sector, giving people all the options and having all the tools because it’s not one thing or the other. If people want to get to abstinence-based recovery we will get them there, if they want to reduce harm that’s what we’ll do for them. People have to have agency over their own lives, we just need to ensure that they have that chance. There’s still such a way to go, but it’s all moving in the right direction.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe