The fight against racism goes on: interview with leading human rights lawyer Aamer Anwar

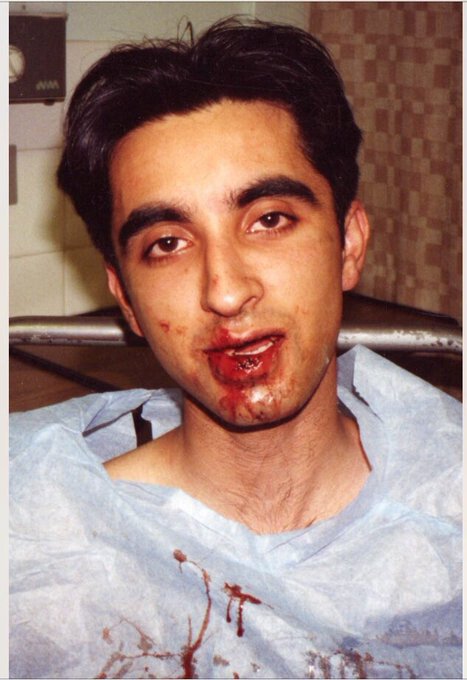

There’s a photograph that hangs on the office wall of the human rights lawyer Aamer Anwar that serves as a daily reminder, if one was ever needed, of why his fight goes on.

The image is of him as a student, wrapped in a paper sheet, his mouth swollen and bloodied, and his front teeth broken. It’s a picture taken 30 years ago, after Anwar was wrestled to the ground by police for illegal flyposting in Glasgow’s Ashton Lane. And it is a permanent record of an encounter that changed the course of his life.

Having come to Glasgow from his hometown of Liverpool to study to be a mechanical engineer before a career in the RAF beckoned, that one terrifying experience catapulted him into a different world of political protest, academic study and ultimately into the law.

During the fracas with the police, he was pushed to the ground, had his teeth smashed and was kicked repeatedly. He says the officer told him at the time: “This is what happens to black boys with big mouths.”

Well, that black boy with the big mouth would not be silenced. He successfully took civil action against the force and, four years later, it was found an officer had assaulted him in what appeared to be a racially motivated attack. The officer was suspended and Anwar was awarded £4,200.

“That moment did change my life. I became a radical campaigner and after some 25 attempted arrests, five court hearings, several arrests and four years of legal fighting, I won my civil action against the police, the only person of colour to ever do so in Scotland,” Anwar tells me.

“From then until now I have learned justice is never given to you, but always fought for.”

Three decades on and Anwar is one of the country’s most prominent human rights lawyers, championing some of the highest profile and complex cases in Scotland, including those of Abdelbaset Al-Megrahi, the Libyan convicted of the Lockerbie bombing, Surjit Singh Chhokar, the Lanarkshire waiter who was murdered in a racially motivated attack, and more recently, Sheku Bayoh, from Kirkcaldy, who died after being restrained by police officers and whose family believe would still be alive today had he been white. He is also currently representing the Rangers player Glen Kamara, who claims he has suffered racial abuse on the pitch.

Anwar and I speak in the days following the conviction of US police officer Derek Chauvin for the killing of George Floyd by kneeling on his neck for nine minutes in a case that appeared to be a global tipping point in terms of racial prejudice. The guilty verdict coincides almost to the day with the 28th anniversary of the racially motivated killing of the British teenager Stephen Lawrence, and follows hard on the heels of the much-awaited publication of the report of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities which was set up in the wake of the Floyd killing under the chairmanship of Tony Sewell to explore issues of race in the UK. It controversially concluded that institutional racism no longer exists in Britain.

There was an immediate outcry to its publication, with critics warning that the Sewell report could turn the clock back on the fight against racism in the UK by 40 years. And the day before Anwar and I talk, a leaked report revealed that a group of serving judges in England and Wales claim that racial discrimination and bullying in the judiciary is preventing the promotion of ethnic minority judges to any of the top jobs.

It’s a contradictory set of circumstances that swirl around us, and Anwar is angry. Some might say that is his default position. He would say, with good reason.

“Just the other day I did a podcast with Imran Khan, an old friend of mine who was the lawyer for the Stephen Lawrence family, and we did it on the official Stephen Lawrence Remembrance Day, just an honest chat between two friends of how we both felt at recent events, and the words that struck me was Imran saying that he feels despondent. Why? Because it almost feels like the clock has been turned back.

“You look at the Sewell report and then you look at events that have happened around George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement, the President of the United States speaking about structural racism and launching an inquiry into the police, yet, in this country, the UK Government’s response is that racism doesn’t exist. I said quite flippantly to Imran after the Sewell report, why didn’t they just abolish the term ‘racism’, and then they can scream from the rooftops that we don’t have racism anymore because the word has gone.

“On the other hand, the verdict in the George Floyd case meant a great deal because I think family all around the world whose loved ones have lost their lives to police violence, who have lost lives to racial violence, and for individuals who’ve campaigned – and for me, it feels like I’ve been fighting racism all my life and definitely for the last 30 years – the verdict was a vindication of our fight but I don’t mind saying, I was glued to the TV, and it was with a feeling of fear as you were watching it.

“I was telling people I knew that we were not going to win, and I use the words ‘we’re not going to win’, because we’ve got so used to watching racist police officers walk away, never see justice, no matter how much evidence there was against them, so this was a verdict that was important to all of us. When that first ‘guilty’ was read out, it was a feeling of shock and actually tears because I was so overwhelmed by that feeling of joy, that feeling of relief. It was relief, more than anything.

“It reminded me almost of the feeling in 2016 when I was in the High Court in Glasgow waiting for the verdict in the Surjit Singh Chhokar case. We’d fought for nearly 18 years to get justice for the family of Surjit, who was a victim of a racist murder, and that overwhelming feeling of relief when the verdict came, it’s hard to explain. People asked me at the time, are you and the Chhokar family going to be celebrating and I said, there is no celebration, it’s just quiet relief and a satisfaction that justice had been done.

“It was the same with the Floyd verdict. I thought it was a very important moment for those people who were new to the politics of anti-racism, who were the younger generation who had stood up to say black lives matter. And that overwhelming blow that was struck for justice, it meant a great deal to them, because for an old-timer like me, you know, you get used to the defeats.

“People always ask me, how do I keep going, keep fighting, and I say that for every 100 defeats, there is that one victory, and that one victory powers you to carry on, and on, and on. But for many of us, and Imran and I agreed on this, it’s just business as usual. We will carry on; we will keep fighting.

“And when you look to the United States and see what happened with the verdict in the George Floyd case, I had to temper my reaction when I spoke to quite a few young people who were going, this is great. I had to say, it is great but it’s still business as usual. You can’t just simply move on, thinking the battle has been won, because just down the road, another black person was just shot dead by police, Daunte Wright, and you also had that young girl shot dead just as the verdict was being read out, it was almost like a message being sent out from the status quo, from a racist police system, saying we will just carry on.

People always ask me, how do I keep going, keep fighting, and I say that for every 100 defeats, there is that one victory, and that one victory powers you to carry on, and on, and on.

“So yes, one case was won and that one case was always very important because it galvanised a movement, and it made people think that you can win, and it gives hope, but when you strip it all away, how much has changed?

“It is the sixth anniversary of the death of Sheku Bayoh who died in Kirkcaldy in police custody and I spoke to Kadi, Sheku’s sister, just after the George Floyd verdict, and she was crying. She was relieved but there was also this feeling that she doesn’t believe she’ll ever see justice for her brother.

“We should remember that in this country since 1969, for every person that has died in police custody, not a single police officer has been convicted of murder, of culpable homicide, of manslaughter, and that so when we look across at the United States, and somehow we think we’re better, well, actually, the statistics here are worse, because as Kadi said at the time, at least four police officers would stand trial within the space of four weeks in the George Floyd case but within the space of four years of campaigning, no police officers are to stand trial in this country for the death of Sheku Bayoh.

“Now when you compare and contrast, of course, there is anger. The family is angry. I am angry. And there is disappointment that in this country that when people marched, when they carried the placards saying black lives matter and put pictures of George Floyd in their windows, that so few have said the same about Sheku. Why is he not a worthy victim? Did he not have the right to life? So yes, I welcomed the verdict in America, but it was a bittersweet moment.”

No one has been held responsible for Sheku Bayoh’s death, no charges have been brought.

However, following a campaign led by Anwar on behalf of the family, an independent public inquiry was opened at the end of last year. It will examine all the circumstances around the death and whether race was a factor. It is expected to last several years.

I ask Anwar why he believes that there has been so little political outcry at the death of a black man in police custody in Kirkcaldy.

“I think they all lack courage. They need to grow a backbone. If it’s about party commitment or loyalty, then let’s look at the SNP, the party of government, their MSPs will always look to their leaders to see how they should respond and I say this with respect, because Nicola Sturgeon, the first minister, met with the family within the first year and Humza Yousaf, the justice secretary, and he happens to be a friend, ordered the first inquiry into race in policing ever in Scotland, so he did that, he delivered that, but I was very conscious of the fact that when we were looking to, for instance, SNP MSPs to get behind the campaign around Sheku, there was abject silence.

“However, no party escapes criticism. There was a handful of individuals from the Labour party, that spoke up, like Claire Baker. I can’t remember anybody from the Liberal Democrats speaking up initially. I couldn’t remember anybody from the Conservatives speaking up. I think there was a handful from the Greens.

“But there was almost silence in terms of a response, in terms of political support, it just wasn’t forthcoming, and to a certain extent, that is the fault of the propaganda that came out from the very start from the police and the media, and it then takes so much time to explain to people the facts. But I see it as basic cowardice from our politicians, that failure to speak up, to question, to interrogate, because how can you speak up about George Floyd in America but not speak up about Sheku Bayoh in Fife? It’s rank hypocrisy to call out the name of George Floyd, but not to call out the name of Sheku Bayoh.

“People like to think racism isn’t a problem in Scotland and when I first arrived in Glasgow back in the 1980s, it seemed like a segregated city. The only people of colour that I saw was the Pakistani community and people would say to me that we didn’t have racism here, that we’ve got sectarianism, but we don’t have racism, we were all Jock Tamson’s bairns.

“I didn’t really understand what that meant until years went by and it frustrated me as I became political, became involved in student politics and started to fight racism, how people seemed to find it easier to fight apartheid, several thousand miles away in South Africa, but when it came to racism on their own streets, within our own communities, within their own schools, within their own institutions, they didn’t see it as a problem.

“I remember watching the then home secretary, Jack Straw, standing on his feet to welcome the Macpherson report into the Stephen Lawrence case and recognising that there was institutionalised racism within the police and I was despondent at the time, because whilst people were celebrating that in England and Wales, I was despondent as an anti-racist campaigner in Scotland because people were saying we don’t have the same problems here. And the reason they were saying we don’t have the same problem was because we didn’t have a lot of black people, as if having a large community makes it a problem.

“So, I was disappointed at the time, thinking, what does it take for people to wake up to the problems on their own doorstep and bizarrely enough, two weeks after the Stephen Lawrence inquiry came out, the first trial of the Chhokar case collapsed and the racist killer walked free. That galvanised probably the biggest anti-racist movement we have ever seen in the history of this country. Neville and Doreen Lawrence backed it, the press were crammed in, and we were sitting in the headquarters of the STUC, the whole trade union movement united like a force of good to back the Chhokar family and to drive for a second trial. Ultimately, it took 18 years to get that, but we did it.

“I think there’s almost this mythical thing in Scotland that racism is a problem in England but we’re fine. We like to talk about the abuse of human rights by the Tories in England. We like to talk about their abuse of asylum seekers. We like to talk about Priti Patel, and all of that as if we are exceptional. I say, why don’t we have a look at what’s happening on our own doorstep, we have the scar on this nation. We see black people, asylum seekers, attacked.

“It was only a few months ago that the Daily Record talked about the racist diatribe that Humza Yousaf, Anas Sarwar, and myself, as the three so-called most prominent Asians in Scotland, face on an hourly basis, whenever we look at our phones.

“Many people in the community do almost feel as though the clock is being turned back and I want to see more done from the party that’s in government. I don’t want to see tokenistic responses. I don’t really care if you’ve put up BAME candidates, because the reality is, they are still just candidates. How many have we got in parliament? It’s an abject disgrace that we only had, until this election, two people of colour, two males, two Asians, in the Scottish Parliament.

“So, what does it mean? To me, what it means is that in 2000, when I stood outside the steps of the High Court in Glasgow and came out of the second trial of the Chhokar case, and I stood on the steps and said that we have two systems of justice at work in this country, one for the rich, and a very different one for black people and the poor, that the Crown Office operated like a gentleman’s colonial club, relatively unchanged for 400 years, that we have no black senior police officers, no black High Court judges, no black senior prosecutors, that nothing much has changed.

“So, yes, we need the BAME candidates but there is no point in BAME candidates standing on the shoulders of giants, you know, getting there because of the blood, sweat and tears and the sacrifices made by others, to simply shut up and to be complicit in the silence. I don’t want to see Uncle Toms in any of the parliaments in Scotland, or in England and Wales, for the sake of it.

“What I want to see are people who will fight for our community. And I am tired of having to be the one that always calls out these things. This isn’t just about deaths in custody, this isn’t just about racist murders, it’s about the racism that perpetuates in our institutions, jobs, in the education system, in political parties, in our communities, it’s about the daily grind of the corrosive impact of racism.

“I do not want my children to grow up having to experience what I had to experience. My son’s 13 now and my heart thumps faster when he goes out because I can give him all the advice when he goes out the door, tell him what to avoid, to stay away from groups, what to do if somebody says anything racist to him, but I’m also concerned about a police officer’s approach and what he should say and how he should react. And that horrifies me, that all these years later I should have to give that advice to my son. That is heart-breaking because I genuinely want things to change. I want things to change for my children. I want things to change for my children’s children.

“I’ve been a lawyer now for over 20 years and if I’m being honest, I still spend my life looking over my shoulder at the institutions, thinking that if they can give me a kicking, if they can drag me down, if they can kick me out, they will try their damnedest best to do so because I’m still seen as what the police described me as when they smashed my teeth out - the black boy with the big mouth.

“I don’t want that future for my children, my son, my two daughters. I want them to grow up to be valued on the basis of the people that they are, the content of their character, not be judged by the colour of their skin. Not to walk in a room, as I do still to this day, knowing whether somebody likes you or doesn’t like you, is assessing you, judging you, dealing with you, talking to you, based on your colour. I still feel that and I don’t want my children to have to feel that. But equally, I don’t want their dreams to be shattered one day because I brought them up to think they can succeed regardless, be anything, and for them to then think, I didn’t succeed because of the colour of my skin.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe