Branching out: Scottish Labour needs to show voters it can chart its own path

When members of Scottish Labour meet for the party’s annual conference in Glasgow this weekend it will be amid a renewed sense of optimism about the future. The party has spent the past decade in the political doldrums in Scotland, failing to find both a message and a leader that cuts through to the public.

If the situation is different now – and that certainly seems to be the case – it’s less about what Labour has done and more about the unravelling of its opponents. At UK level, nearly a decade and a half of Tory rule is coming to an end, voters desperate for change after being saddled with the legacy of austerity and Brexit. Meanwhile, the Conservative Party is threatening to tear itself apart, with those on the right of the party seemingly intent on undermining Rishi Sunak just months from a general election.

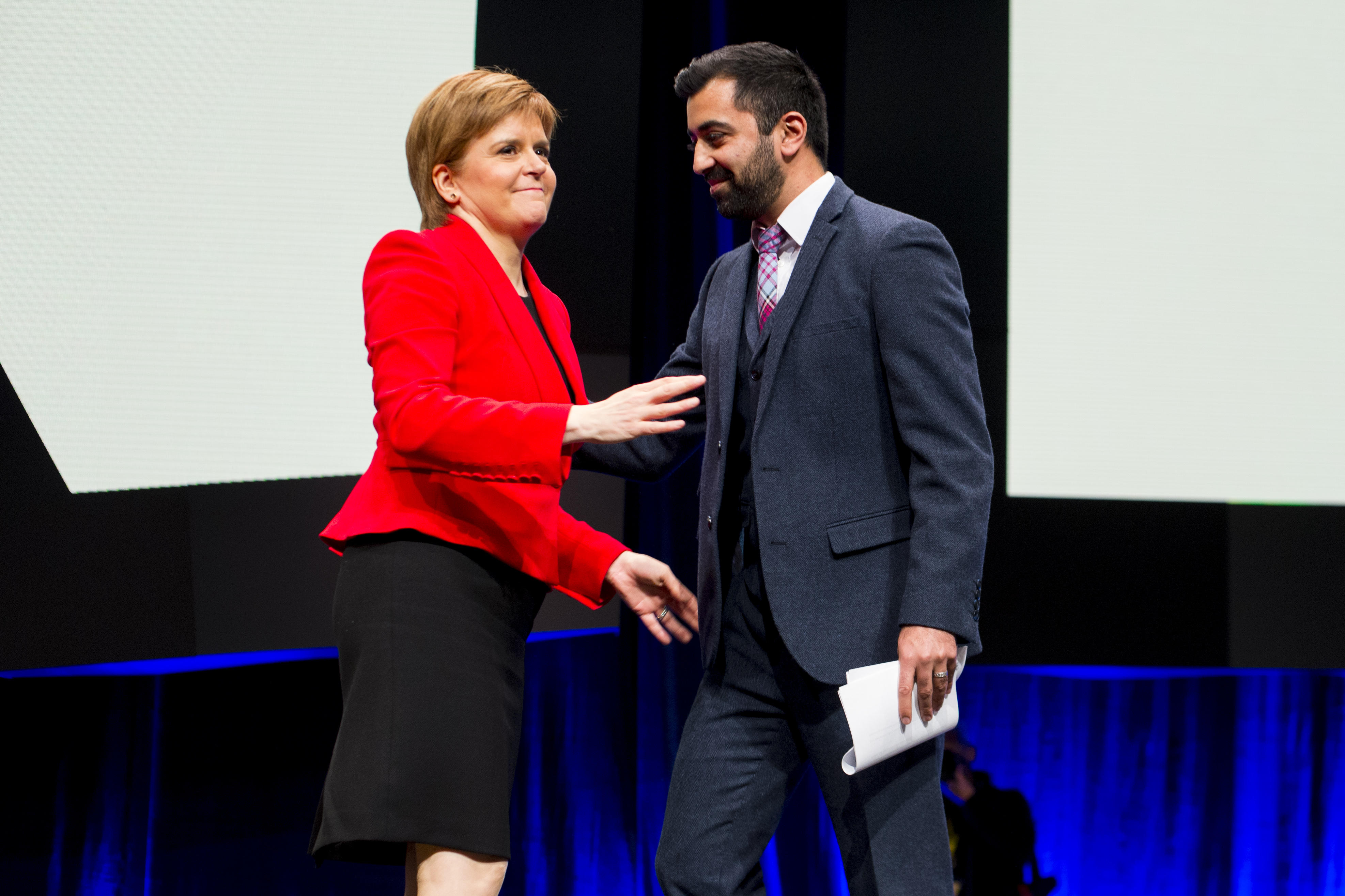

In Scotland, too, the situation is markedly different from the 2019 general election. Not only have we lived through Covid, but the SNP’s star is on the wane. Five years ago, Nicola Sturgeon’s party cruised to a stunning victory, securing 48 out of Scotland’s 59 parliamentary seats. But a good deal of water has passed under the bridge since then, not least Sturgeon’s resignation in the early part of last year. Not only is Humza Yousaf less popular than his predecessor but he’s also been tarnished by the mess she left behind, namely the long-running police investigation into the party’s finances and the controversy over the systematic destruction of messages dating from the pandemic. It’s a legacy that outgoing Paisley MP Mhairi Black, a once staunch supporter of Sturgeon, recently referred to as a “slightly poisoned chalice”.

That’s not to say Labour should expect things to go all its own way, but the signs are positive for the party. Polling carried out last month by Survation for lobbyists True North found 34 per cent of Scots plan to vote for the party at the general election, compared with 36 per cent for the SNP. According to analysis by Professor John Curtice, that would put the parties neck and neck at Westminster on 23 seats apiece. The SNP has a four-point lead in voting intention for the next Holyrood election, according to the same poll. It’s a sign of how low the party’s expectations currently are that a poll projecting the loss of 20 MPs was seized on as positive news. A separate Ipsos poll found Labour had cut the SNP’s lead to seven points on general election voting intention – down from 10 points in November.

Curtice says it’s currently “nip and tuck” between the two parties in the run-up to the general election. “Pretty much every opinion poll points to Labour having a substantial majority south of the border,” he says. “In Scotland, a couple of dozen seats for Labour looks feasible but you have to remember that so many of the seats will be marginal. If the SNP can just widen that lead a little bit, get it back up closer to 10 per cent, Labour will find themselves without necessarily a great deal [of seats] at all. Conversely, Labour could overtake the SNP and have shown consistent signs of being able to do that. It’s all dependent on quite small movements.”

Speaking to the BBC recently, Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar said he hoped his party could be “competitive” in around 25 seats at the general election. “I want us to do even better in the polls; I want us to persuade even more people,” he said. “Times have changed significantly in Scotland. Before it was the SNP that relished elections and the Labour party feared them – it’s the opposite now. There’s only one political party in Scotland that can’t wait for that general election and it’s the Scottish Labour Party.”

But if Scottish Labour has benefited from the travails of its political opponents, it continues to suffer from the perception that it is merely the party’s “branch office” north of the border – a term memorably coined by former leader Johann Lamont when she resigned in 2014. In recent months it has found itself having to stave off a series of attacks over policy positions taken by UK leader Keir Starmer as he does his best not to alienate floating voters in England ahead of the election.

The SNP’s Stephen Flynn had arguably his finest moment as Westminster leader when in November a motion calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza led to a Labour rebellion, with frontbenchers including Jess Phillips defying the party whip. While the motion was ultimately defeated by 294 to 125, a total of 56 Labour MPs defied Starmer’s order to abstain. Figures in the party had urged MPs not to “undermine the party in Scotland” by voting with the SNP.

There was another headache for the party in Scotland when Starmer appeared to praise Margaret Thatcher, describing her as a leader who effected “meaningful change”. In an article in the Sunday Telegraph, in which Starmer also praised former Labour prime ministers Tony Blair and Clement Attlee, he wrote: “Margaret Thatcher sought to drag Britain out of its stupor by setting loose our natural entrepreneurialism.” It was the sort of comment Sarwar and his Scottish colleagues could have done without.

Scottish Labour dominated the early years of the Scottish Parliament | Alamy

Scottish Labour dominated the early years of the Scottish Parliament | Alamy

The problem for Labour is that while its Scottish leader has grown in popularity, most voters north of the border remain at best deeply ambivalent about Starmer. The MP for Holborn and St Pancras has sought to “bomb proof” his party in the run-up to this year’s election, U-turning or backing away from anything which appears to put some clear blue water between Labour and the Tories. That has often left Sarwar in an invidious position such as last summer when Starmer refused to scrap the so-called ‘rape clause’ should Labour come to power. Introduced by father-of-five George Osborne in 2017, the two-child cap limits benefit payments unless a third child was conceived as the result of a sexual assault. Introduced as a means of encouraging parents into work, it has instead been blamed for pushing a rising number of children into poverty. Scrapping the cap had been part of Labour’s 2019 manifesto under Jeremy Corbyn until Starmer rowed back on the commitment.

Starmer’s U-turn was red meat for the SNP, putting Sarwar in the awkward position of having to defend something he had previously campaigned against. The Scottish Labour leader found himself in a similar situation when Labour dropped its earlier position on self-ID following the controversy over the Scottish Government’s attempts to reform the Gender Recognition Act, legislation which Sarwar’s MSPs had backed before it was blocked by the UK Government.

As recently as last month, Labour was disappointing those who want the party to be more radical and make a more definite break with 14 years of Tory rule. Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves said there was no plan to reinstate a cap on bankers’ bonuses after it was scrapped by the Conservatives last year. It was an open goal for the SNP which accused Starmer of being “on the side of the wealthy elite, not ordinary working families”. And on reform of the House of Lords – Starmer had previously pledged to abolish the second chamber – there has been an apparent rowing back, with reports suggesting a Labour government will instead make only limited changes in its first term, including legislating for the abolition of hereditary peers – something the party promised in its 1997 manifesto.

But James Mitchell, professor of public policy at the University of Edinburgh, says the differences between voters in England and Scotland are often overplayed, with Starmer’s tacking to the centre unlikely to be as damaging for Scottish Labour as some assume.

“What is more important is the more significant question of the relative autonomy of Scottish Labour,” he says. “Labour has suffered from a perception that it lacks autonomy. Anas Sarwar has sought a course that signifies a willingness to be different including demanding the end of the two-child benefit cap… It will not hurt Scottish Labour to have different policies from those pursued by Keir Starmer south of the border – that was the purpose of devolution.”

Mitchell says Sarwar must plot a course that portrays him as both autonomous and willing to stand up for Scotland without picking fights with London at every opportunity. “In essence, he needs to show Scottish Labour is the party of devolution both in how the party operates as well as how it will govern,” he says.

If there are challenges for Labour north of the border, there are also plenty of positive signs. At the recent Rutherglen by-election, the party not only retook the seat but enjoyed a swing from the SNP of over 20 per cent. Labour took 59 per cent of the vote – up 24 points from the 2019 general election. While there were plenty of local factors at play, not least sizeable levels of unhappiness at sitting MP Margaret Ferrier after she breached Covid laws and refused to stand down, the result does point to a party that’s on the way back after more than a decade spent on the peripheries of Scottish politics.

Since 2007, when the SNP first came to power, Scottish Labour has had seven leaders: Wendy Alexander; Iain Gray; Johann Lamont; Jim Murphy; Kezia Dugdale; Richard Leonard and Anas Sarwar. Having dominated Scottish politics for most of the last century and the early years of the Scottish Parliament, the past decade or so has been the party’s wilderness years. In 2015, the party returned just one MP in Scotland – Ian Murray – at the general election. The following year, Labour slipped to third behind the Tories in the Scottish Parliament as the constitutional debate and the future of the UK came to dominate the political agenda in the wake of the 2014 independence referendum.

Despite being on the winning side in 2014, Labour was given a bloody nose at the general election the following year. In the years since, everything has been viewed through the constitutional prism. Now, nearly a decade on from the referendum, there are signs the constitutional question is no longer dominating Scottish politics in the way it once did. While support for independence remains high – 48 per cent of voters said they would vote Yes in the recent Survation poll and 53 per cent in the Ipsos survey – the route to a referendum looks blocked. After Nicola Sturgeon failed in her attempt to secure a vote through the Supreme Court, the SNP wisely dropped its Plan B, namely that the general election would be a de facto referendum on leaving the UK. No less confused, the current message appears to be an acceptance that Labour will win the election but that a vote for the SNP will make “Scotland’s voice heard” in Westminster.

The SNP has suffered a series of setbacks since Nicola Sturgeon's resignation | Alamy

Mitchell says the constitutional question no longer has the “primacy” it once had. “We are seeing some supporters of independence willing to vote Labour,” he says. “They now see that the Scottish and UK Governments were playing politics during the pandemic and continue to do so in its aftermath. A section of independence supporters want change and having given the SNP a chance to deliver change – whether constitutional or delivering on promises – they are now looking elsewhere.

“While the SNP leadership produces yet another white paper and claims it wants an independence referendum, it still has not come close to having a convincing and credible response to many of the issues raised in 2014. Brexit highlights differences between Scotland and the whole of the UK but it also undermines the case for independence relative to the situation pertaining in 2014. So it is not just the SNP’s lamentable record in office but the wider context that has acted against the SNP.”

Indeed, as the constitutional question has faded from view, more of a spotlight is being shone on the SNP’s record in government, with concerns over the state of the education system and NHS waiting lists. Recent controversies including the deletion of WhatsApp messages and now ex-health secretary Michael Matheson’s £11,000 iPad data roaming bill haven’t helped. With Sturgeon no longer in charge, the party seems less capable of fending off attacks when it comes to its 17 years in power.

“Whereas back in 2021 and a long time beforehand evaluations of the Scottish Government’s record didn’t seem to be associated with the willingness of people to vote for the SNP again, now it looks as if it might be,” says Curtice. “People who are concerned about the state of the health service who voted for the SNP in 2019 are now somewhat less likely to say they will do so again.

“There are doubts about the SNP as a political institution and its record in government – a less popular leader and a more divided party. Put those things together and there’s a broad sense this is not the party that people voted for in 2019 or 2021.”

If the SNP has had its annus horribilis then for Scottish Labour, things can only get better. After growing complacent during the years it was dominating Scottish politics, the party now looks to have learned its lessons. It remains to be seen how many voters are willing to forgive and forget.

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe