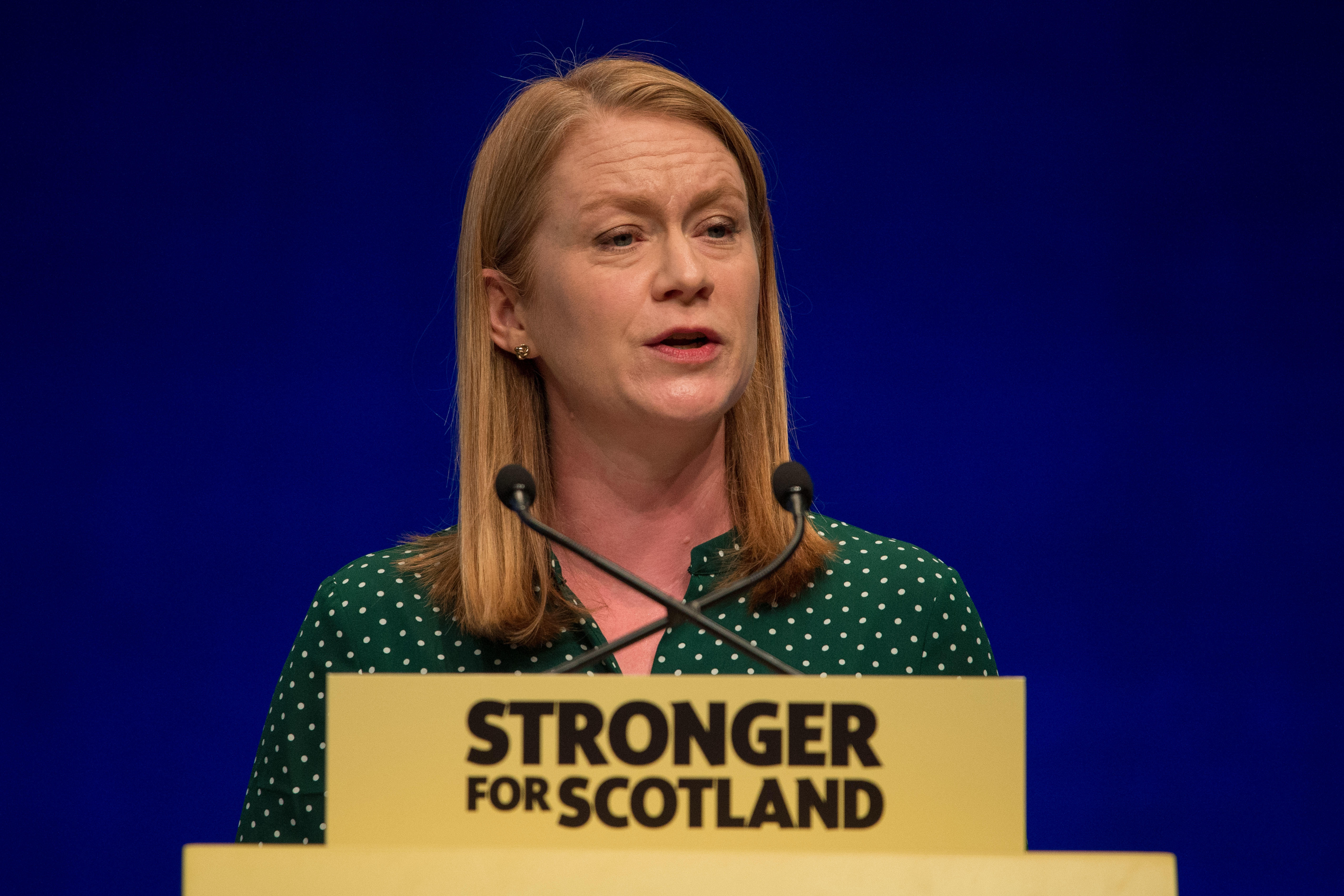

Shirley-Anne Somerville: Every day a school day

Education secretary Shirley-Anne Somerville isn’t sure if the teachers at her daughters’ school know who she is, beyond being another parent.

The Dunfermline MSP took over the portfolio in May last year during what she calls a “very strange time”, 15 months into the pandemic and following an exams results crisis that triggered serious questions about the strength of our systems, and whether or not they’re serving young people.

Fast forward another 16 months, and it’s not clear when that strange time will end. When Holyrood sat down with Somerville, it was the day that the EIS teaching union confirmed its members would strike over pay, with its general secretary Andrea Bradley stating that teachers were “increasingly angry over their treatment” by employers and the Scottish Government.

If her girls’ teachers didn’t know who Somerville was before, it’s hard to imagine that they don’t now. “I’ve never asked them if they’re aware of my job,” she says. “They’ve never said if they are; they’re very professional.”

And anyway, Somerville says her dual roles – parent and politician – allow her greater insight into the system she now heads. The portfolio spans all levels of education, taking in everything from anti-bullying measures and the closure of the attainment gap to digital inclusion and curriculum reform.

Reform is very much on Somerville’s mind right now. She announced a “national discussion” on the future of education in June, with a view to establishing a “compelling and consensual vision” for learning. By that time, it had already been announced that the education and exams agencies would be scrapped and replaced, with the beleaguered Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) broken up and a new inspection agency created.

That came after a report from the OECD backed the much-criticised Curriculum for Excellence, but said there was too much focus at senior levels, and a separate paper by Professor Ken Muir made a clutch of recommendations, concluding that there is a need for change in “the way that policy itself is developed, implemented and overseen”.

That report, Somerville said, presented a challenge to create a system “which can genuinely put the learner at the centre”. To do that, she says, she needs to be careful who she listens to. Since taking office, Somerville has been accused of being “invisible” by some critics (pro-independence blogger Wings Over Scotland) and “missing in action” by others (the Scottish Conservatives). “People will say what they say,” she says, adding that “listening directly to children and young people and teachers” is what matters.

“It’s been 20 years since the last national debate on Scottish education. This is our opportunity to build on these good foundations, talk about what’s important to learners, teachers and parents and use that to exemplify everything that’s great about Scottish education and where we can do better,” she says, adding that she tends not to “spend that much time on Twitter”, where you don’t have to look far to see criticism of Scotland’s education system.

“I was reflecting on that at a conference recently, speaking to some headteachers, and they were asking me, ‘what can we do about the fact that we always hear everything’s bad?’” she says. “This national discussion is an opportunity to actually shine a light on what things are good.

“Yes, I value what is said by my other colleagues in the Scottish Parliament, but the real test for any politician is how open they are to conversations with those that matter most. For me, that’s children and young people. If you have a system that puts them at the heart of what you are doing, and that can respond to the needs of staff – that is where I should be spending my time.”

In just a few months, Professor Louise Hayward will publish her independent review of qualifications and assessment, and Somerville says work to create the new qualifications body, schools inspectorate and education agency will draw on the approach taken by Scotland’s social security experience panels, which took insight from people with direct personal experience of the benefits being devolved to Scotland under post-referendum changes.

As cabinet secretary for social security and older people, Somerville oversaw that process and the set-up of Social Security Scotland, which made almost £164m in direct payments across 11 benefits in 2021-22 and received praise from clients in an annual satisfaction survey. Almost all of those who had been in contact with staff “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they had been “treated with kindness” and 93 per cent said the experience was “very good” or “good”. It’s something that gives Somerville “an exceptional degree of pride”. “There was reform process I saw through which is paying real dividends,” she says. “People can say what they like about me; I spend very little time on that.”

Born in Cardenden, Fife, Somerville was “the shy and quiet person in pretty much all” of her classes at Kirkcaldy High, and says former classmates would be “surprised” by her transformation, which can involve being “exceptionally robust, if required”. She’d no grand career plan, but did know that she “wanted to go to university” and “campaign on issues that I was passionate about”. She did both, and made the latter into her career, entering the Scottish Parliament via a staff job with former SNP Highlands and Islands MSP, Duncan Hamilton. Somerville had read economics and politics at the University of Strathclyde and spent a short spell as a housing officer. She later took a campaigning role at the Chartered Institute for Housing, and another at the Royal College of Nursing.

She won election on the Lothians list in 2007, becoming the SNP’s deputy whip and acting as parliamentary aide to John Swinney. Somerville lost her seat in 2011 when a surge in constituency votes reduced the SNP’s success on the list, but she gained another in 2016, when she won Dunfermline from incumbent Cara Hilton of Labour. In between, she took a role with housing charity Shelter Scotland and became deputy chief executive of the SNP. And between those, she joined Yes Scotland as director of communities in the run up to the 2014 referendum.

It’s a path the young Somerville had never envisioned, not least due to growing up in the days before devolution. “I spent a couple of months as a housing officer, then the Scottish Parliament opened and there was all this opportunity to work for the SNP, and I jumped at the chance,” she says.

“Politics was never on my mind,” she says of her early ambitions. “The idea that you would ever get a job through it at that time was nowhere near. Without a Scottish Parliament, there was no way I thought you would ever be able to have this type of opportunity. It wasn’t folk like me that made politicians,” she goes on. “I was reasonably young, and female, and coming from a reasonably working class background.

“I spent all this time studying for a career, then left it remarkably quickly. Part of that was because what I realised was that I wanted to not be part of a system, but to campaign for change. I wasn’t satisfied with just being part of a process, I wanted to challenge how that process could get better. The way housing was done at the time, I was never going to be satisfied. It’s not the case now, but I was struck when we were in that point of handing somebody a £50 B&Q voucher as they stood in a barren, empty flat with no support around them, and wondered why tenancies failed. I thought, if this is the best we can offer people I don’t want to be a part of it.”

Somerville credits her urge to campaign to her parents. Her dad was “horrified” when she joined the SNP at 16, she tells Holyrood, in a Kirkcaldy where “they used to weigh the Labour vote in”. Her family wasn’t political, she says, but her parents “did instill in me a belief that if you wanted to do something, and you had the chance to do something, you took it”.

It was a time, Somerville says, when “you would keep your activities with the SNP off your CV rather than trying to make something of them”. However, those activities took her into Young Scots for Independence (YSI), the SNP’s youth wing, and into the company of fellow activists including Nicola Sturgeon and Shona Robison. She was also a member of the Student Nationalists, and the networks she found would be pivotal to her political and personal development. “I know I wouldn’t have got to the place where I am without the support of women who were in the YSI, or men when I was in the Student Nationalists. They had more belief in me than I did,” she says.

“At some point this will come to an end, whether that’s at a point of my choosing or not,” she says of her parliamentary career. “After politics, that’s what I’ll get back into, campaigning. I’ll never lose that wish to campaign and to change and be a thorn in the side of whatever government is in power at that point.”

Will that be in an independent Scotland? “Absolutely,” Somerville says. “I have no doubt that independence will happen. Certainly, we are in a process about when that will be, but there is an inevitability about independence. The only way we can possibly take hold of the opportunities that I saw when I was that 16-year-old in Kirkcaldy growing up is with independence. What my role in that is, is entirely up to other people.”

For now, Somerville’s role is to see out the reform process and stabilise relations with the teaching workforce. A 24-hour walkout was announced for 24 November after a five per cent pay offer was rejected, with further industrial action also planned. Appearing on the BBC’s Good Morning Scotland, Somerville said the Scottish Government was “absolutely determined” to work with council body Cosla to get closer to the 10 per cent sought by the union.

“We have huge sympathy for public sector workers, with high inflation and the cost-of-living that we have,” she said. “But we do also have to bear in mind the reality and the context. The Scottish Government has a fixed budget. It cannot change taxes in the year, its reserves have been fully utilised.

“If we’re looking to fund public sector pay offers, that money has to come from somewhere else in the budget.”

In his emergency spending review earlier this month, Swinney announced £615m in cuts on areas including Covid testing. The pandemic hit education hard, and Somerville is mindful that its effects continue to be felt. “It’s not like Covid has gone away; it’s very important to recognise that,” she says, but she wants to “start looking forward” and at the “really amazing good practice that goes on right across Scottish education”. She cites schools like Dunoon Grammar, which was named “world’s best school” for community collaboration, and Methilhill Primary, which is making strides on digital skills. “It’s a fantastic portfolio to have and I was really excited to get this opportunity to take on one of the biggest portfolios in government, but at a time when we had been through a couple of years of education that none of us could have ever possibly imagined.

“I couldn’t set foot inside a school for the first year. That was my biggest frustration. Nothing beats being able to get into a school and speak to children and young people directly, seeing the teaching and learning that’s going on. That’s the most important part for me.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe